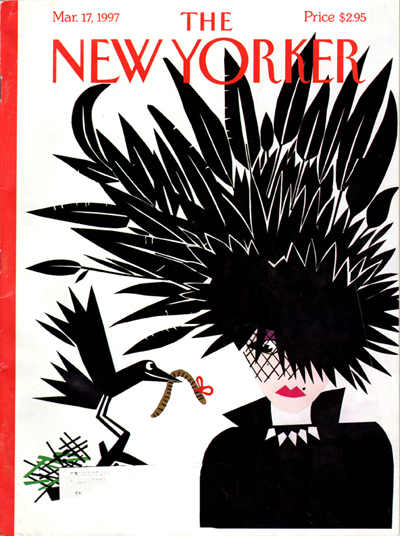

The New Yorker, 17 March 1997, pp 70-75

The Road To "Crash"

It was a shocking novel when it was published twenty-four years ago. Now it's the most controversial film of the year. Why did J.G. Ballard write it?

By Tom Shone

On a fine summer's day in the early seventies, the English writer J.G. Ballard stepped out into the back garden of his house in a London suburb, took in the view, and dropped some LSD. He never repeated the experience, and said later that it was a “classic bad trip.” The amazing thing is that LSD sent him on any kind of trip at all. For Ballard was the kind of guy who wrote this for a living: "I think of the absurd crashes of neurasthenic housewives returning from their VD clinics... of sadistic charge nurses decapitated in inverted crashes on complex interchanges; of supermarket manageresses burning to death in the collapsed frames of their midget cars before the stoical eyes of middle-aged firemen." He was the kind of guy who, having written that, would go back and change "supermarket manageresses" to "lesbian supermarket manageresses," just for fun.

That passage is taken from Ballard's bad-trip classic "Crash," which explores the erotic significance of the automobile accident -- "the meaning of whiplash injuries and roll-over, the ecstasies of head-on collisions." So speaks the narrator, who, in the course of the book, and with the help of some like-minded characters, works this stark sex-death equation through all its possible permutations. He has sex in his car. He crashes his car. He has sex in the spot where he crashed his car. He has sex in his crashed car with his girlfriend. Then with the woman he crashed into. And every idle moment he fills with fond meditation on the "complex geometries" of the dented fender, the “gymnastic ballet" of multiple pileups, windshield ejections, and other "optimum auto-deaths."

Ballard's book rammed into public consciousness in 1973, before backing off into cult status. Now it has been made into a movie by David Cronenberg, although the reception of Cronenberg's “Crash” has had a more fitful stop-start rhythm. The movie was shown in Cannes last year to a mixed chorus of boos and applause; it won a Special Jury Prize, despite the reported loathing of Francis Ford Coppola, the jury president. After it was screened again, at the London Film Festival, in November, the British Secretary of State for National Heritage, Virginia Bottomley, called for it to be banned; the film still awaits certification in Britain. And it reaches American cinemas next week only after a lengthy wrangle between Ted Turner, who owns the film's distributor, and Ted Turner, who thought the film might encourage people to have sex in their cars while driving at high speed.

All of which finds Ballard, at age sixty-six, in buoyant high spirits. He is no stranger to controversy, on the contrary, he is controversy's friend and longtime companion. In Britain, a publication of his entitled “Why I Want to Fuck Ronald Reagan” was one of the prime exhibits in a 1968 obscenity trial; Ballard was due to take the stand until the defense attorney realized that he would make a better case for the prosecution. He has always prized Conrad's dictum "To the destructive element submit yourself," so it makes perfect sense that his first question to me, upon sitting down to Sunday lunch at London's Halcyon Hotel, would be a gleeful "Have you been sent to attack me?"

He seems a little crestfallen when I answer that I'm mostly trying to put him in context for American readers. "And what context is that?" he asks. I admit that I can't actually see much in the way of context. "Good!" he says. "Keep it that way!" Lunch with Ballard is a distinctly nerve-racking affair. He is a model of good-humored geniality, but his volume level when he is broaching such topics as the possible eroticism of car-crash wounds takes no heed whatsoever of surrounding diners. Next to us, a family of four make increasingly unenthusiastic progress through their Sunday roast; instead, they're huddling over it in whispered conference: Who on earth is this man? The answer is simple: like it or not, they’ve been seated beside Britain's only living prose surrealist.

Earning that status is quite an achievement, given the natural resistance to surrealism on the part of both Britain and prose, and has required equal amounts of perversity and guts. In a 1982 essay, "What I Believe," Ballard laid out his credo: "I believe in the beauty of the car crash, in the peace of the submerged forest, in the excitements of the deserted holiday beach, in the elegance of automobile graveyards, in the mystery of multistorey car parks, in the poetry of abandoned hotels." Public affection had a hard time blooming in Ballard's blanched, lunar landscapes; but in 1984 Ballard published an autobiographical novel, "Empire of the Sun" -- detailing his childhood internment by the Japanese in wartime China -- which won him a new and broader readership. Then came the enormously successful movie version of the book, which makes Ballard the only author ever to have been adapted for the screen by both Spielberg and Cronenberg. It's a huge leap -- from film's greatest childhood dreamer to its most pitiless chronicler of adult nightmares -- and among the greatest compliments the cinema has paid one man's imagination. But then Ballard has always taken such extremes in stride, in both his life and his work, and he demands that we do the same, if only to keep up.

James Graham Ballard was born in 1930, in Shanghai, the only son of a wealthy businessman. His family was part of a community of expatriate Britons living in one of the city’s suburbs – a small corner of ersatz England, filled with Tudor-style mansions that could have been airlifted over from Surrey or Dorset. After the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, when Ballard was eleven, he and his family were sent to a civilian prison camp at Lunghua, about ten miles south of Shanghai, where they remained for three and a half years. Ballard says that he thoroughly enjoyed the camp: free of his parents’ control, he kept himself hyperactively busy -- running errands, playing bridge. Years later, for a column called "The Worst of Times," which appeared in the Independent, Ballard selected as his own worst experience not his imprisonment at Lunghua but his family's return, in 1946, to England -- a place Ballard had until then only read about in books, and had imagined to be a "sunlit, semi-rural land with beautiful rolling meadows and village greens and ivy-clad rectories." Instead, he later wrote, he found "a London that looked like Bucharest with a hangover" and a gray-faced race of people who "talked as if they had won the war, but behaved as if they had lost it."

He went to Cambridge, trained to become a doctor, then joined the R.A.F., and that shifting of perspective on humanity -- from a worm's-eye view to a bird's-eye view -- runs right through his fiction: in his books, either you're a distant speck in an engulfing landscape or you’re making a big mess on somebody’s windshield. "Crash" has always had a big cult following in France and Italy -- countries, it will be noted, that have a markedly more relaxed attitude toward both experimentation in the arts and safety on the roads than Britain's -- but when the odd Citroen-load of French "Crash" freaks made the pilgrimage to Ballard's house in the seventies they were disappointed to find not the crazed arts terrorist they'd expected but a courteous Englishman in striped shirt, jacket, and sandals, with three kids and a golden retriever -- his only concession to abnormality being a pet rat. "Lovely creature," Ballard recalls. "Never bit anyone.”

Ballard's house is to be found in Shepperton, a far-flung and supernally quiet suburb of London. Outside in his driveway is a battered Ford Granada. (Yes, he's had sex in a car, many times, but has crashed only once; he didn't like it nearly as much.) He lives alone now; his wife died suddenly, in 1964, of pneumonia. His children, whom he reared single-handed, have grown up and moved away. He has a longtime girlfriend, Claire, to whom he periodically proposes, and who gave him, as a sixtieth-birthday present, the unicycle that sits in the hall.

Ballard tells me that he can ride it, and it seems as good a vehicle as any for negotiating the cramped confines of his house. A prodigiously large potted palm dominates most of the front room; a pile of shoes cower in the corner, planning their getaway; an exercise bike holds out no such hope. In the back room, where Ballard works -- in longhand, in spiral-bound notebooks -- a large orange sofa is busy collapsing in on itself. His copy of the medical textbook "Crash Injuries" now lives upstairs ("Oh, that -- that's just a joke"), but among the books that remain below are a copy of the Warren Commission report (shelved with fiction) and monographs of Gaudi, Dali, and the Belgian surrealist Paul Delvaux, one of whose paintings, destroyed in the blitz, Ballard has had reconstructed using a little of the money he earned from "Empire of the Sun." It is far too large to be hung on the wall -- it's almost as big as the wall -- and so simply leans against it, providing anyone willing to risk the sofa with a fine view of some naked women standing in a garden. Surrealism may never have taken off in Britain, but it has taken quiet, firm root in the house of J. G. Ballard.

"Drink?" he asks, a single glass in his hand. A decade or so ago, he would have joined you. Or, rather, you would have joined him: he used to start on the whiskey at 9 A.M. and continue through the day. He's got it back to nightfall now, but his body language, like that of many reformed heavy drinkers, still carries within it a distant chemical memory of drunkenness. When he is ascending the conversational foothills toward one of his favorite theories -- "the Normalizing of the Psychopathic," say, or "the Death of Affect" (he seems to speak in capitals a lot) -- his eyes widen a little madly and his laconic drawl rises to an excited declamatory pitch, his white hair shaking loose. The over-all effect is of the Ancient Mariner if he'd been an ex-R.A.F., whiskey-and-soda kind of chap.

His first novels, published in the early sixties, were science fiction, but of a highly selective sort. Ballard passed on the genre's rockets and robots but took up the offer of earth-shattering cataclysm, and in "The Drowned World," "The Wind from Nowhere," "The Drought," and "The Crystal World" he successively flooded, sandblasted, dry-roasted, and petrified the globe. The British have always had a talent for disaster stories -- possibly a flamboyant offshoot of their talent for self-deprecation -- but one pecularity of Ballard's disaster stories is that they seem to embrace apocalypse with open arms. Take this passage from "The Crystal World," the title of which speaks for itself:

What most surprised me . . . was the extent to which I was prepared for the transformation of the forest-the crystalline trees hanging like icons in those luminous caverns, the jeweled casements of the leaves overhead, fused into a lattice of prisms, through which the sun shone in a thousand rainbows, the birds and crocodiles frozen into grotesque postures like heraldic beasts carved from jade and quartz.

Or, for that matter, take any of Ballard's heroes, who survive the worst only by heading straight into it. At the end of 'The Drowned World," the hero journeys not north, to safety and dry land, but south, into the terminal heat of a vast swamp. "The original American publisher suggested that I change the ending," Ballard recalls, laughing, "as if somehow I'd mislaid my compass." He had, of course: Ballard's bearings were internally, not externally, calibrated. "It is inner space, not outer, that needs to be explored," he wrote in 1962, in New Worlds, the magazine that helped launch Britain's new wave of science fiction. "People have accused me of being pessimistic as a writer," he says now. "But actually all these early novels of mine -- and all my fiction, right to the present – they’re all stories of psychological fulfillment. My heroes all find themselves in a disintegrating world, and they construct a personal mythology which will give meaning to their lives and then they embark on a journey in which they try to find themselves in terms of this mythology."

Ballard's own mythology, meanwhile, was ready for a makeover. The late sixties found his fiction holed up in a snaking concourse of spaghetti junctions and concrete high-rises, while his imagination went walkabout in hyper-reality. In his 1970 novel, "The Atrocity Exhibition”, whose chapters include "You: Coma: Marilyn Monroe," "The Assassination of John Fitzgerald Kennedy Considered as a Downhill Motor Race," and "Love and Napalm: Export U.S.A." -- Ballard seemed intent on taking the entire twentieth century personally. “We live inside an enormous novel," he has written. "The fiction is already there. The writer's task is to invent the reality." His best work of this period started life as just that: a big hunk of reality -- or, rather, three big hunks of reality. In 1970, Ballard towed three crashed cars into an art gallery, London's Arts Laboratory; arranged for a topless girl to interview visitors on closed-circuit TV; and sat back to soak up the response -- a mixture of nervous laughter and casual vandalism. "That was my green light to write 'Crash,'" he says. Further spur, if any were needed, came in the form of one publisher's note on the book. "This author is beyond psychiatric help. Do not publish," it read. 'Which," Ballard says, "I regarded as complete artistic success."

To call "Crash" a shocking book gets you only halfway there, for shock is its subject as well as its object -- both its means and its end. It is also a novel in shock, its form buckling under the weight of the author's exhaustively reiterated obsession. It has all the problems with suspense that you'd expect from a book about a bunch of characters with sublimated death wishes, and its sentences frequently collapse in a pileup of abstractions ("For him these wounds were the keys to a new sexuality born from a perverse technology"), but its lack of momentum is, with typically jackknifing logic, the point. It's the world's first slow-motion novel, aspiring to the stasis of a Muybridge photograph -- which is one of the reasons that it is a book better contemplated than read. Reading the thing may be like boring through concrete, but from a safe distance its central conceit acquires a wicked Swiftian glint: the nicest thing you can do to the human body and one of the nastiest, swapped.

Ballard's fiction, post-"Crash," gives the impression of an imagination going easy on itself. But by the time of the 1979 novel "The Unlimited Dream Company," in which he turned Shepperton into a green and luxuriant sexual utopia, his imaginings had acquired a mellow, spongiform texture, his defamiliarizing tricks having now been worn smooth with familiarity: too many dreams, not enough limits. Then, just as his books looked as if they were slipping into the inky fingers of the diehard cultists, Ballard went and did something truly shocking: he told us a little about himself.

In a notably odd career, "Empire of the Sun" proved the crowning oddity, if only because that career now appeared to have run in reverse. Indeed. London's literary world acted as if a new writer had been born in its midst, and greeted the book with a mixture of riotous acclaim and outright puzzlement: Why had he held on to this for so long? It was almost as if William Burroughs, in his sixth decade, had suddenly turned around and knocked out "The Naked and the Dead." Ballard's book is now widely considered the best British novel about the Second World War. There are few contenders, partly because the war never reached Britain in any dramatically satisfying way, thus opening up a gap -- which writers have struggled to close -- between civilian and frontline experiences. In Shanghai, Ballard saw them thrown into a dizzy, disorientating embrace.

The most haunting images in the book are to be found in the two periods of interregnum, before and after the boy's imprisonment at Lunghua, during which Shanghai couldn't quite seem to decide whether it was at war or at peace -- a drained swimming pool, its floor littered with the detritus of summer parties past; a sports stadium filled with cars and illuminated by the distant light of the Nagasaki bomb. Ballard writes, "It was not that war changed everything -- in fact, Jim thrived on change -- but that it left things the same in odd and unsettling ways." Reading the book, you realized that the surrealism of his earlier work had been less an artistic strategy than a simple survival plan, a way of mapping the sights he had seen: chapters are headed "The Abandoned Aerodrome," "The Stranded Freighter," "A Landscape of Airfields," "The Refrigerator in the Sky." You can easily imagine Steven Spielberg -- who once envisaged alien visitation in terms of a renegade vacuum cleaner -- buying the rights to the book on the strength of that last chapter heading alone.

He was not, as he is portrayed in both book and film, separated from his parents, but he was pretty much a "free spirit" at Lunghua, he says, running wild "as teenage boys do in any large slum." His parents had none of the normal systems of leverage over him -- treats to give or to withhold -- and Ballard was anxious, one guesses, to avoid the fact of their powerlessness. "Watching adults under sustained stress is a great education for children, even more so when the adults are one's own parents," he says. Instead, he idolized both those who best coped with that stress (the Americans in the camp) and those who inflicted it (his Japanese captors). He puts this down, in part, to a young boy's natural hankering for hero worship. "The Japanese were the heroes of the hour, at least for the first few years of the war," he says. "There was an element of Stockholm syndrome, too. You begin to identify with and collaborate with the people who are holding you hostage. The whole war was holding me and the others hostage. One tends to develop a rather strange psychology in order to cope with this."

This strangeness was a little lost on Spielberg: in Ballard's identification with the Japanese he saw a proffered flower of international friendship; in his obsession with airplanes he saw a fairly routine symbol of flight and transcendence -- a chance for another of the filmmaker's trademark shots of a boy's rapturously upturned face. In the book, however, the young Ballard's gaze has the beady and benumbed fixity of someone staring down death ("Everyone in Lunghua was dead. It was absurd that they had failed to grasp this," he writes), and his obsession with airplanes seems bound up in this, too: he survived by fetishizing the very technologies that might one day kill him.

"One does tend to fetishize them," Ballard explains, "because that empowers you in turn, gives you some sort of sense of control. You become obsessed, as I did, with the shape of fuselages on Mustang fighters and B-29 bombers. It gave me the illusion of some sort of control over these instruments of my own private destiny. Even though they were bombing the hell out of the airfield next to the camp. One bomb misdirected would have put an end to my existence." And so, in the words of one of Ballard's favorite films, he learned to stop worrying and love the bomb.

Hence the ambivalence his science fiction displays toward apocalypse: he wasn't lamenting the future; he was memorializing his past. "The fact is, if you like, that the boy in 'Empire of the Sun' grew up in comparatively few years," he says, "and he began to write -- I think, looking back -- fiction that was trying to make sense of what he'd seen as a boy." By the age of fourteen, Ballard had witnessed most of the ways we have devised to bring lives to an end: he'd seen people beaten, beheaded, bombed, shot, strangled. "Every day, my eyes were opened to a reality which I hadn't previously glimpsed, and that I still think most people in, say, this country, or in the comfortable West, haven't glimpsed."

This certainly explains the messianic tone of his work -- his urgent desire to open his readers' eyes as wide as his were opened – but Ballard is wary of having his work kidnapped by his early life. "I think it’s a mistake to think that everything we produce in our adult lives, whether we're painters or film directors or journalists or novelists, is radically formed by the experience of childhood," he says. "You know, I was happily married, I had three children that I've been very closely involved withas a single parent. I’ve had long relationships with other women that have been very happy and fulfilling. These have been just as important to me." The only gap in this picture is, of course, the one left by his wife when she died, in 1964. They had been on holiday in Spain; she came down with pneumonia; and within days she was dead.

"Hindsight never gives you twenty-twenty vision," he says of his wife's death, continuing with a thought that winds a long way before finally reaching "Crash." "She was so young -- thirty-four -- that I felt a terrible crime had been committed. By nature, against her. And it reminded me of all those terrible crimes that I'd seen during the war in the Far East, and it reminded me in a peculiar way of the Kennedy assassination, which had taken place the previous year and had been televised endlessly, and of the whole culture of sensational violence that had grown up in the nineteen-sixties. What I was trying to do was make sense – I think, I think to some extent, of this meaningless death. If I could give it some meaning, make sense of Kennedy’s death -- all these other deaths -- I could possibly find a rationale for my wife's death."

His hesitations are telling. "Crash" is clearly the work of a man who urgently wants to illuminate the darkest corners of his imagination, as a young boy might illuminate the darkest corners of his bedroom with a flashlight -- so that nothing more can be imagined lurking there. But it makes for a strange act of mourning. There's a princess-and-the-pea quality to the relationship between Ballard's work and his life: the one registering the other's presence with pinpoint accuracy -- Shanghai's paddy fields resurfacing in the images of a flooded London in "The Drowned World," for instance, but through several thick layers of displacement, a lag of years, even decades. "Crash" materialized, after all, during what Ballard calls the "happiest years of my life": the years he spent bringing up his children.

"Again, with the benefit of hindsight, I think I was reliving my own childhood," he says. "Or not reliving my childhood but having a childhood for the first time." When his children left home, the circle was complete: Ballard could return to his own personal year zero and write "Empire of the Sun." At the time of its publication, Martin Amis asked him if the book signaled the end of his "hard-edge" phase. "It probably signals the end of everything," Ballard replied. It didn't, of course. He has gone on writing, but he has had to deal with the considerable problem, faced by few prophets, of seeing many of his prophecies come true. When Ballard writes about environmental cataclysm now, he joins a large chorus: one doesn't need the car to forge a link between sex and death anymore; and the media landscape that so exercised his imagination in the sixties has proved both as sensational and perhaps not quite so threatening as he once thought.

He has, though, found routes of ingress, like a plant pushing up through paving stones. "The Kindness of Women" (1991), a sequel to "Empire of the Sun," sees Ballard safely through the sixties (he writes about that decade as if it were the Third World War he'd been looking for), his wife's death, and the departure of his children -- bringing his story up to the late eighties. You finish it with the satisfying thought that the imagination, far from being a fragile thing, is in fact a tough mental muscle, a stubborn reflex -- a survival mechanism. "That's true in my case," Ballard says when I put it to him. "I think that as a boy I had a very active imagination, and it helped keep me going. It wasn't simply a matter of physical endurance." His voice rises: he has spotted a chance for one last act of provocation. "And it's helped keep me going during another period of privation -- postwar life in England, to this very day. The hazards! Fifty years ago, I had to cope with General Tojo. Now I have to cope with Virginia Bottomley. Will I survive?"

|

|