|

|

|||

|

|||

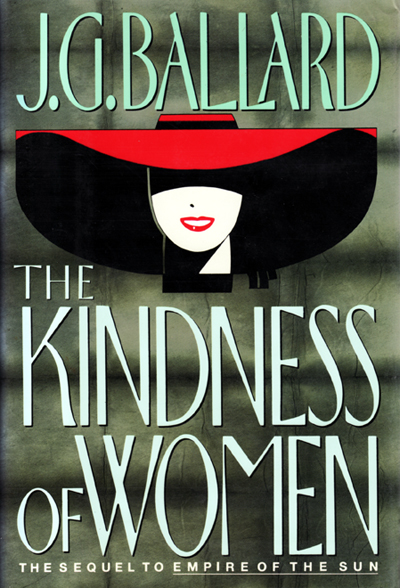

London Review of Books, October 10, 1991 Unlucky Jim Julian Symons The Kindness of Women by J.G. Ballard HarperCollins, 286 pp., £14.99, 26 September, 1991. There is something to be said for encountering some years after publication a fictional work not only popular but critically acclaimed. What is novel in the subject-matter will have become familiarly known, something particularly relevant to J.G. Ballard’s Empire of the Sun, which fascinated some of its early readers and reviewers because it was based on the writer’s childhood experiences while interned in Shanghai during World War Two. And in the case of this book the wave of indignation when it failed to win the Booker Prize has subsided. Its successor, incidentally, The Kindness of Women, has just failed to make thisyear’s short list. When read seven years on from its first appearance Empire seems a remarkable work, although not ‘an incredible literary achievement’ nor ‘the best British novel about the Second World War’, as was said at the time of publication. One would hope that any literary achievement is credible, and Empire is not in any meaningful sense a war novel. It is an artistically artful vision of a child’s self-protective reaction to a life totally disrupted, in part fiction, yet only dubiously a novel. When J.G. Ballard decided to use the material of his early life as basis for a prose work (and the decision must have been difficult and painful), he must have realised that such material could easily be treated in a way distinctly corny. Boy is separated from parents by war, searches for them, is interned, goes on looking, meets them again when war ends — it could be the basis for a TV soap or a conventional tear-jerking film. The book’s quality, dignity, even grandeur, come from the rejection of such too-obvious possibilities. It is told in the third person, the parents hardly enter the story and the family reunion stays undescribed. The sufferings of 11 to 15-year-old Jim are narrated with impersonal coolness and the tone throughout is dispassionate. His experience of hunger, death, occasional cruelty, is the more effective because it is recorded without any attemptat pathos or even emotion. Such level realism could become dull, but never does because the book is also a nightmarish adventure story. The boy’s Christian name carries an echo of Jim Hawkins and even perhaps Jim Dixon — although this is an unlucky Jim. Throughout the book the vivid fantasy of Jim’s imagination colours the darkness and drabness of actuality. He imagines himself a pilot, Japanese and not American because he admires the Japanese. When befriended by two sailors, almost the first thing that occurs to him is that they may want to eat him. There are scenes in the latter part of the book, when Jim is hallucinated by exhaustion and hunger, that owe a good deal to the author’s interest in Science Fiction. Typical of them are a sudden fall of hail after the defeated Japanese have left the Olympic stadium where Jim has remained beside the dying architect Mr Maxted, whose face is ‘speckled with miniature rainbows’, and the subsequent ration drop of tinned and frozen food from what seems to him 'the refrigerator in the sky'. The effect is of a Surrealism that has its Magritte boots bedded in real soil, a unique and powerful product. To put it more conventionally, Empire of the Sun is remarkable because the author has consciously shaped the sensational material of his early life. It is this deliberate shaping that makes it so convincing as a child's approximation and assimilation of terrible realities. And so to women, the kindness of. The new book has a very different artistic strategy. It is told in the first person, so that the effect is one of immediacy, a participatory urgency replacing the distancing device of the earlier work. The first section is set in Shanghai, and the opening scene goes back to 1937 before the beginning of Empire, when Jim (here called Jamie) at last sees the war -- that is, the war between the Japanese and Chiang Kai-shek’s Chinese — come to Shanghai. It is something he has eagerly awaited, imagining it in terms of his toy soldiers drawn up on the carpet. His introduction to the actuality of war, however, comes through a Japanese bomb dropped beside the Great World Amusement Park that kills more than a thousand people. We move on by a jump-cut to Lunghua camp where much of Empire was based, but it is now seen differently. Jamie is in the children’s hut, his friend David Hunter plays hour-long skipping games with the younger children, he feels platonic love for 14-year-old Peggy Gardner, unmentioned in the earlier book. The reunion with his parents in the final chapter of Empire is here expanded a little. ‘Smiling cheerfully, they embraced me as if we had been separated for no more than a few days,’ and Jamie feels they are playing the roles of parents and son, in which they are soon word-perfect. So far as the parents are concerned, they are bit parts. They disappear from this book as, more reasonably, from the earlier one. This is the story of the attempts made by the adult Jamie (he reverts eventually to Jim) to come to terms with his horrific and disorieting Shanghai experience. In a series of jumpcut chapters, with elisions of brief or lengthy time passages between them, we see Jamie as medical student at Cambridge (which he rejects as ‘a glorified academic gift-shop for American universities’), trainee RAF pilot in Canada (he runs out of fuel and crashes his plane while searching for the vanished plane of a Turkish trainee pilot), family man living happily at Shepperton (wife dies in accident), and Sixties experimenter ready for any sexual or social novelty. David Hunter and Peggy Gardner reappear, and images of the Shanghai past haunt Jim, in particular, an incident at a wayside railway station where four Japanese soldiers have tied a Chinese youth to a telephone pole, and while Jim eats a sweet potato and drinks water given him by the Japanese the Chinese boy chokes to death. Some general aspects of the Sixties are suggested through David Hunter’s reckless experimentation which lands him in an asylum, and through the way-out TV projects of a sociologist who ends up trying to make a filmed record of his own death from cancer. The healing process for Jim is completed when his vision of Shanghai materialises a few miles from his Shepperton home in the filming of Empire of the Sun. George Orwell once said to me, apropos of Coming Up For Air, that first person narration should always be avoided. There are obvious exceptions, but this is a pretty good rule where passages of the writer’s life are deeply involved in the fiction, as Orwell’s were and Ballard’s are. Ballard lives in Shepperton, his wife died after ten years of marriage; like his protagonist, he has a son and two daughters. Perhaps it does not matter how close fiction is to the facts of the writer’s life, but the first-person, narration has obvious dangers in the way of sentimentality and pretentiousness which have not been avoided. There is also a sense of strain in the determination to show the links between Shanghai child and adult man, so that incidents like the crashed plane (Jim in Shanghai fantasised about being a Kamikaze pilot) seem not symbolic but contrived. As for portentousness, here is Jim reflecting on his departure from the Air Force: ‘Whatever mythology I constructed for myself would have to be made from the commonplaces of my life, from the smallest affections and kindnesses, not from the nuclear bombers of the world and their dreams of planetary death.’ And here he is after the death of his wife Miriam: ‘I discovered that I had lost not only Miriam but all the women in the world. An unbridgeable space separated me from Miriam’s friends and the women I knew, as if they had decided to isolate me within a carefully drawn cordon. Later I realised that they were standing at a distance, in the nearby rooms of my life, waiting until I had faced my anger at myself.’ Not all of the book is on this vague, woozy level. There are well-written, effective scenes — in particular, a description of a car accident and the passages involving the frenetic David Hunter. But they are embedded in some slack or flowery writing. And the kindness of women? That is all too apparent as Jim beds one after another, describing each encounter in exhaustive and exhausting physical detail. ‘Chang’d loves are but chang’d sorts of meat’ according to Donne, and certainly in Ballard’s book one vulva (‘Deftly she scooped my semen from her vulva’) is much like another. The invariable kindness ofwomen is emphasised when, before Empire’s film premiere in Los Angeles, Jim meets again Olga, his White Russian governess in Shanghai. Now Mrs Edward R. Weinstock — her husband, as she proudly says, a nose-and-throat surgeon — Olga is nevertheless irresistibly moved to run nails across Jim’s chest and undress him, ‘her fingers never leaving my skin asthey moved around my body’. Perhaps he was Lucky Jim after all. |

|||