|

|

|||

|

|||

|

John Baxter: The Outer Child

Some Random Notes on Reading The Baxter Biography of J.G. Ballard "...the fictional aspects have completely drowned any reality that's left, so the fiction is the reality now, people's corporate fantasies now for the first time define the external landscape of our lives so we are moving around in other people's fictions most of our time, we're characters in a gigantic novel." (J.G. Ballard, The Guardian, 11 September 1970) By Rick McGrath OK, the book is open... let's begin! Page 4: Baxter asserts: “truth has no greater enemy than a smooth talker with a good story.” After his accusations of Ballard seeking out Danish porn for nefarious reasons on the very first page, why not go for the liar accusation soon after? And while you’re at it, play up the smooth talker by having an “acquaintance” say, “Ballard is a better off-the-cuff commenter than he is a fantasy novelist”. Wham! And then, for proof, offer up what voices you think may have been on Shanghai radio during the 1930s – “Orson Welles, Conrad Nagel and Franchot Tone”, and then suggest Ballard, then a child less than 10 years old, used them as “models” for an “understanding of the vividness of the spoken word.” Wow. What a genius child! In actuality, Ballard tells us he listened to Flash Gordon on the radio, then music programs for which they phoned in requests. But what’s Ballard’s untrustworthy word against Baxter’s imagination? Page 5: "[Ballard’s] reflexive affability disguised a troubled personality that sometimes expressed itself in physical violence. Given his childhood… it could hardly have been otherwise.” Rather than specific information on this troubled childhood we’re given some odd ideas about Shanghai’s cruel and carnal nature, as if the city were the size of a village, as well as some gossip about JG’s hatred for his younger sister, who was “threatening his relationship with his mother”. A jealous six-year-old... amazing! And the "physical violence" this produced? No examples are given. Use your imagination! And there it is – the first mention of JG being a borderline psychopath. And just in case you think that’s nothing special, here’s a definition: “a mental disorder characterized primarily by a lack of empathy and remorse, shallow emotions, egocentricity, and deceptiveness. Psychopaths are highly prone to antisocial behavior and abusive treatment of others, and are very disproportionately responsible for violent crime. Though lacking empathy and emotional depth, they often manage to pass themselves off as average individuals by feigning emotions and lying about their past.” I’m betting we’re going to be hearing a lot more about those characteristics as this book continues… Page 6: “Even before the war, Jim was harmed by the experience of living as a privileged outsider within a nation of the deprived.” Let’s see… the war started in 1937, so between November of 1930 and the time he was seven, Shanghai somehow imposed some terrible “harm” on him, even though Ballard himself relates many happy memories of living the privileged life, on horses, in the French Club swimming pool, visiting friends, playing war hero in his yard… Even more perplexing, Baxter then insists this unstated mental harm reveals itself in other ways, to wit: “his penchant for sleek cars and sleeker women, and a taste for sudden death and the machines that inflict it.” So, here it is – being a little white rich kid among poor asian people makes you desire hot cars, hot women, violent deaths and killing machines. Even if this preposterous suggestion is true, tell me, how does this make a young Ballard any different than any other young, hormonal man? In actuality, JG never owned a sleek car, wasn't noted for sleek women (save Claire Churchill), was absolutely crushed by his wife's sudden death, and never came close to a killing machine, unless a clunky training aircraft counts... Page 7: We discover JG didn’t like his parents much… there’s proof of craziness! Baxter asks what the problem might have been and admits to being confused, as “superficially, his childhood appears tranquil, even pampered.” What an understatement – the family had hot and cold running servants and lived in a big Tudor mansion! He did suffer the usual britkid upperclass snobbery -- raised by a nanny, overdressed all the time, distant parents, church, school, uniforms, be seen and not heard, blah, blah -- but you can dislike your parents for lots of reasons, some oedipal, some intellectual, some social, some egotistical. In any case, there's no proof (aside from JGB himself) that there was any dislike until Lunghua, when Mom and Dad lost JG, probably to puberty. Or so JGB tells us. It's a bit of a leap, though, to say strained or uncaring family relations mainly express themselves in pathologic terms. Page 11: OK, this is getting boring, but one comment: yes, life was very formal for these Brits, but “Adult indifference to children was axiomatic. With infant mortality high, it didn’t pay to become too attached”. Huh? This is the 1930s in the world’s fourth-largest city! No doctors for the rich? “They took little notice of Jim, meeting his numerous irritating questions with a blank stare and silence”… where did Baxter get that bit of damning family history from? Was he a secret boarder, disguised servant? This smacks of information from Empire of the Sun. Page 21: Lunghua. I sat down again last night and re-read Betty Barr's and Peggy Abkhazi’s books of their accounts at living in Lunghua. Interesting. I also re-read the extremely short chapter on Lunghua in Baxter’s book... even more interesting. Let’s begin with the ladies:  Of the two books, Peggy’s is the most detailed and mature, as she was a 40-something single woman in the “loose women’s” dorm. Betty, who was born in 1933, was obviously too young to keep notes, but her mother kept a diary of the days and Betty basically dives into them... what’s interesting about her account is her family was also in G Block, but sadly she doesn’t really talk about life there, aside to describe her room as being way too small for all the stuff they brought from home. Both cover basically the same ground, but in different detail. Betty’s memories are more childlike, as she tries to plug herself into her mother’s diary, most of which she doesn’t use. Both are fixated on food — perhaps adding more credence to my theory that Empire is about Hunger (in all its forms) -- the weather, keeping clean, endless work schedules, and “the riot”, when internees stopped the Japanese from beating one of their men in a sports field. Betty doesn’t talk about anyone specifically, but Peggy drops a lot of names... she also is obviously diplomatic when it comes to complaining, especially about her dorm mates... she's also very concerned with finances, and gives a running update on how much inflation is degrading the occupation money. Both also note how odd a sight it is for the “taipans” (male bigshots) to be doing hard manual labour — smashing up bricks for pathways being the usual... Of the two books, Peggy’s is the most detailed and mature, as she was a 40-something single woman in the “loose women’s” dorm. Betty, who was born in 1933, was obviously too young to keep notes, but her mother kept a diary of the days and Betty basically dives into them... what’s interesting about her account is her family was also in G Block, but sadly she doesn’t really talk about life there, aside to describe her room as being way too small for all the stuff they brought from home. Both cover basically the same ground, but in different detail. Betty’s memories are more childlike, as she tries to plug herself into her mother’s diary, most of which she doesn’t use. Both are fixated on food — perhaps adding more credence to my theory that Empire is about Hunger (in all its forms) -- the weather, keeping clean, endless work schedules, and “the riot”, when internees stopped the Japanese from beating one of their men in a sports field. Betty doesn’t talk about anyone specifically, but Peggy drops a lot of names... she also is obviously diplomatic when it comes to complaining, especially about her dorm mates... she's also very concerned with finances, and gives a running update on how much inflation is degrading the occupation money. Both also note how odd a sight it is for the “taipans” (male bigshots) to be doing hard manual labour — smashing up bricks for pathways being the usual...Betty’s recollections are in a book called ‘Shanghai Boy, Shanghai Girl’ (Old China Hand Press, Hong Kong 2002) co-written by her husband, George Wang, who grew up just outside the old city, and gives a pretty good look at what it was like to live at the other end of the Ballard spectrum... Betty was born in Shanghai, and her few chapters in Wang’s book tell her whole life, with just 30-odd pages of interest to us. Peggy’s story is in two books: ‘A Curious Cage’ (Sono Nis Press, Victoria 1981) and later reprinted as ‘Enemy Subject’ (Alan Sutton, Oxford, 1995). Both editions have introductions by S.W. Jackman, but Enemy Subject boasts a forward by Ballard himself... Ballard writes: “All the sights and smells of Lunghua camp rush through the pages of Peggy Abkhazi’s remarkable diary, as if a window had suddenly opened in the small room that I shared with my father, mother and sister in G Block fifty years ago. Reading ‘Enemy Subject’ I feel a stronger sense of returning to the camp than I did when revisiting Lunghua in 1988. Everything is here: the stench, the boredom, the fierce winter cold and stifling summers, the moody Japanese guards and equally unpredictable fellow internees. “Peggy Pemberton-Carter, as she was in Lunghua, taught me French in the camp school, and I wish that I could remember her in person. Her diary suggests a woman of determined character as critical of herself as she is of the other prisoners who share her dormitory hut. She seems always aware of the paradoxes that govern so much of human behaviour. In Lunghua she found that affectation of any kind was soon stripped away, revealing the true personality beneath the veneer, but also that ‘the liars are often generous, and the greedy ones are very clean…’. “The portrait she paints of Lunghua coincides almost exactly with my own memories, though our perspectives were very different. I was a boy in my early teens, and she a mature woman without the responsibilities of husband or children. I assume that this gave her the freedom to remain detached from the often desperate life around her and the mental space to reflect on the lessons that internment taught about human nature and its response to boredom, hunger and the enforced company of those one detests. “Readers will notice that the diary’s tone changes during the years, from the confidence of the opening entries to the creeping depression that dominates the last year of the war. It is important to remember, as one tries to visualize the prisoners’ feelings at the time, that no one in Lunghua expected the war to end in August 1945. My own parents, and the adults I met in the camp, all assumed that the war would last at least another year, if not longer, a grim prospect as the food rations fell and people succumbed in greater numbers to malaria. I have always been aware that my parents had far harsher memories of internment than the cheerful ones I carried with me from Lunghua. “Few British civilians, compared with those of our Allies, endured enemy captivity during the Second World War and ‘Enemy Subject’ is an invaluable record of the courage and stoicism displayed by almost all the British men and women interned in Lunghua during those frequently painful but always extraordinary years.” So... lots of info and a sort of twist by JG, who intimates there were other stories to be told by those who didn’t have the freedom to remain “detached” nor the “mental space to reflect on the lessons” deprivation creates in humans... unfortunately JG doesn’t elaborate on his cheerful perspective (we assume the kids ran wild, but Betty insists even kids had chores, albeit not tough ones... she tended the goats). And what about Baxter? He conjures up five whole pages on those three unbelievably formative years, and basically he lifts and separates from Peggy’s book. Page 21: “Buddhist pagoda, with a giant and threatening statue inside”... Buddhist temples are usually built around a golden statue of Buddha — hardly a scary sight, although temples could also include statues of famous warriors... regardless, pointless editorializing on Baxter’s part. Page 21: “loose women” is explained in Peggy’s book as a function of the Japanese mind... the women were single, so unattached, so loose. Page 21: “To Jim... alarming, but exciting new world”... he has no idea if it was alarming or exciting... a guess from Baxter. Page 21: “He viewed Lunghua in the way an animal raised in captivity might regard the wild into which it was being introduced”... we’re talking about a 12-year-old upper class kid here, folks, not some feral force in a field of sheep... where is he getting this idea? From Empire of the Sun, of course... fiction to fit Baxter’s exterior purpose. Page 22: Neither Peggy nor Betty reference any suicides at camp, but Baxter says there were. Page 22: Baxter says Ballard claimed to have malaria (in Miracles of Life JG says none of his family caught malaria) but he doesn’t believe it because “his ‘attacks’ often coincided with a troublesome commitment he wanted to avoid”... where does this accusation of malingering come from? Wasn't the young Jim supposed to be hyper-active? Page 23: The line about eating greyhounds... Highly unlikely... How many dogs would it take to feed 1700 people? But Baxter is making this up from a website he found in which a young internee is told the “grey meat” in her stew is greyhound. I’m sure the fact the meat was grey and the dog is grey is the let’s-have-fun-with-the-kids rationale behind this. Peggy’s not too keen on the “stew”, either, but mentions the stew often had tripe, a whitish-grey meat. Shanghai did have the superbly-named Canidrome, which could seat 50,000 (mostly westerners), and it ran until 1949 when the communists turned it into a prison, but you have to figure it probably shut down when Europeans got locked up in 1943. So, there would have been dogs available as food. But given what Peggy, who worked in the kitchen, says about the meat they did get – all farmyard variety -- I’d say it’s another Baxter leap into the speculative... anything to add a jolt, eh? Page 24: Baxter says the camp’s food has almost run out when Hiroshima was bombed. Not true. Peggy reports they received food parcels April 1, 1945, but were hungry on May 31... on June 17 more food arrived, and on August 11 she says, “we are living very well these days”. Baxter says after the bomb the residents awoke to find the Japanese gone... “shortly after, US planes dropped canisters of food”... more historical nonsense, as the Japanese left on Aug 16, and it was on Aug 28 the US dropped food... is 12 days “shortly after”? Baxter also leaves out this: in one camp a canister killed a Chinese woman and wiped out buildings; the canisters, food and even the parachutes caused arguments among those dividing them up, and the drops were stupid, as food had already been arriving by US trucks... why drop canisters, Peggy asks a US military official. His response: “Well, we can’t deprive the boys of their fun”. Page 24: Baxter says, “there were almost no escapes” from Lunghua, but there were so many commandant Hayashi was replaced and both Peggy and Betty go on and on about the punishments they suffered in recompense. Page 24: Baxter relates the story of JG’s “most embarrassing event of a long life”, about the time he had to run the length of the “barracks” in front of other internees and the guards. As David Pringle points out, this factoid is in fact taken from something Ballard said in one of his mini-interviews: What was your most embarrassing moment of the war? Missing roll-call by a few minutes in the camp and having to run down the corridor past all the English families standing to attention outside their rooms while the Japanese guards blew on their fingernails. I’ve been punctual ever since. (Ballard, “Leading Questions,” Sunday Express, 20 August 1995.) Of course, JG and family were not in barracks, but a 2-story brick housing unit with rooms, doors and a hallway. And, of course it wasn’t the most embarrassing event of his “long life”, either! Page 24: Baxter says JG made few friendships among the 300-400 children in Lunghua. Where does that info come from? Irene Duguid says the children ran in packs (as always), and JG was part of a group. Page 24: Baxter makes it sound as if there’s 50 US seamen lounging around all day and JG loiters around them with a chessboard. I’m not sure why these guys would be excused from the camp’s pervasive and extensive work regimen (no one else was), but Baxter apparently assumes it’s like the movie. After that Baxter retreats to plot summaries for Empire the movie and book. Youth over! Page 63: The flight school in Moose Jaw, Canada. While I’ve sniggered through an amazing number of purely subjective accusations -- based on nothing concrete — this is simply funny! First, Baxter says London, Ontario is “near Niagara Falls”. Two seconds on Google maps shows otherwise – London is 237 kilometers from the Falls, to be precise. Toronto and Detroit are much closer. Second, apparently Moose Jaw is located in the “tundra” of Saskatchewan. Huh? Who knew you could grow all those crops on ground in which the subsoil is permanently frozen, even in the blistering summer! Amazing... Page 65: The Iroquois Hotel in Moose Jaw from The Kindness of Women is actually in Saskatoon. Baxter stole his description right from the web: “Albany Hotel (1906): “Originally named the Iroquois Hotel, the business was renamed the Albany Hotel in 1912 after an extensive enlargement and alteration. Over the decades, the Albany gained a reputation as a “seedy” hotel and was the scene of many violent crimes. It closed in the late 1990s, and was acquired by Corrections Canada. It now serves as a halfway house for federal offenders.” Baxter also claims the average temp in Moose Jaw in December is -16ºF. In actuality, it’s +20ºF. Page 121: Baxter says Ballard said he would write a story, “in which an amnesiac man would lie on a beach, attempting to define the essence of his relationship with a rusty bicycle wheel — an ambition which... he never pursued.” Duh... that’s the ending of The Assassination Weapon! “He lay on the sand with the rusty bicycle wheel...” Page 133: Baxter mis-observes the advertiser’s announcement ad concerning B&D (Neural Interval). He sees the sadistic outfit as a real bathing suit and obsolete snorkeling gear... hah... the bathing suit is latex or leather, the snorkel is jammed against her face, she’s wearing a neck collar and her hands are bound in fetishistic gear... are his eyes wonky? Page 148: More rants about JG’s lack of neatness — western bourgeoisie anality at its tongue-clucking best -- and more of Baxter’s contradictions, as we’ve already waded thru innuendo about how formal and upper-class clean Jim’s pre-teen years were, and then the relative squalor of Lunghua, then the squeaky regimens of school, then the dingy London flats, etc. Baxter would be better served linking Lunghua to Shepperton, and not Shepperton to “dirt”... JG lived a physical life in landscapes much like his work, much like Dali painted the weird hills around his home. Page 170: Baxter claims no real publication would accept JG’s ad/announcements because of “ineptitude in art”. That’s an unsubstantiated opinion that reveals malice. They would be much more liable for exclusion because of their content, not how that content is organized. This was the 60s! Homage to CC would certainly have been accepted... the others... probably not. Page 248: Baxter claims alcohol played a role in Ballard’s decision to write The Unlimited Dream Company as a “wildly visionary work” in 1976. That is purely malicious conjecture, but it plays along with Baxter’s ongoing thesis that JG was basically pissed all the time, as well as marshaling all his advertising expertise in an endless series of “rebranding” exercises. Wow, an amazing amount of this book is plot summary! Baxter’s not bad at it, but all he wants to find are literary sources and real people Baxter thinks JG has used as characters. Interesting, but Baxter is intellectually incapable of folding these insights into a cogent analysis of the books. The Milton bit about The Unlimited Dream Company is a great example — Baxter’s entire thesis rests on character Blake being Blake’s Milton, so he chooses porno writer, med student and Jesuit from character Blake’s first self-descriptions and assigns them as Reprobate, Redeemed and Elect, as per the poem. Unfortunately, character Blake is a lot more than that -- a student who tries out fertility rites, mercenary pilot, zoo worker, inventor (man-powered airplane), aircraft cleaner. I also get the feeling Baxter thinks that Carlos Castaneda is a real anthropologist! Hah! What an odd little cobble-together of a pastiche this book is! A number of things stay with me: 1) Baxter’s insistence Ballard is a psychopath... c’mon, this basically lumps him in with serial killers. Or politicians. The less malicious might even say, “interesting character”, or “English eccentric”. It's all relative, though, isn't it? We're all uniquely crazy in our own ways. Baxter seems to try to make a moral decision about any and all, real and imagined, of Ballard's personality quirks. JG ain't Jesus, so what kind of repressed "normalcy" is Baxter using as his ideal? (2) JG’s life as an extension of the adman’s sense of creating and recreating a “brand”... absolutely insane... as Ballard himself says, he "ran away" from advertising (I can imagine him chafing at the creative restrictions), and already knew his fame would make him another of the "corporate fantasies" he so obsessively explored in The Atrocity Exhibition. Given his sales and resistance to writing offers, one can only surmise Ballard saw himself as an artist, a self-pleasing storyteller who tended to apply the same invertive techniques to different everyday scenarios. You can’t spend three months as a junior copywriter on a bottle of lemon juice and consider yourself an advertising expert, no matter how much talent you have. Like anything else, it needs practice. As my analysis of Ballard’s attempts at advertising shows, he may have been interested in it as an art form with pop roots, but his own creations reveal JG may have had a product to advertise, but he is oblivious to marketing concepts like target groups and selling points... or even letting us in on what the ad is about! If anything, JG’s associations with ads really never got past his youthful enjoyment of the form and art at Lunghua... he talks about shiny cars and American design, but he remembers the pictures, not the headlines. If anything, I think Ballard would have been happier as an ad designer than copywriter, anyway... Project For a New Novel is an exercise in layout, not narrative, and the Advertiser’s Announcements likewise are design-heavy, with the placement of headlines & copyblocks dictated by the art. From a Ballard/Martin Amis interview in 1984: "And so began Ballard's worldly "career". But of course he was one of life's surrealists - a natural misfit. He read medicine at King's College, Cambridge. He was interested in Freud, Sartre, Camus: 'My fellow undergraduates hadn't heard of them. Neither had the dons.' Thrown out of King's, he read English at London. Thrown out of London, he became a trainee pilot in the RCAF. Thrown out of the RCAF, he ... 'The only thing I wasn't thrown out of was advertising. After I'd been in advertising for a while, I suddenly realised that I hadn't been thrown out of it.' What did this tell him about advertising? 'It told me run, don't walk. I threw myself out.'  (3) If a person’s basic personality is fixed by age seven (Seven Up, etc), then Baxter misses the boat on JG growing up on Amherst Ave, and doesn’t get Lunghua, either. I’ve talked with three people who were at Lunghua, and one of them remembers JGB as an outrageous story-teller in the camp, although her memory may have flipped and she’s also remembering the movie/book of Empire. Regardless, JG’s youth is a history only JG has revealed, and given they're all gone it looks like we’ll never really know how he was psychologically formed, or whether or not he was a petulant, lonely, overdressed, clever kid keenly aware of the adult world. Is a picture worth a thousand words? The confident, fat-faced kid balancing on his bike looking at us from the cover of Miracles of Life says a lot, as I don’t see any parental fists encouraging that Mona Lisa smile. That this is all lost now is something JG himself appreciated. As he told me in 2007, “In an odd way it’s quite reassuring that everything has changed so much — the Shanghai I knew, along with 31 Amherst Avenue and Lunghua camp, only survive inside my head”, and, apparently, Baxter’s imagination, as he uses JG’s 1991 return to Lunghua for a BBC documentary -- Shanghai Jim -- as an opportunity to show JG’s allegedly psychopathic response to his room — “I entered puberty here” -- as all he has to say. So much emotional complexity, so much information, swept aside by Baxter. In actuality, if Baxter had really watched all of Shanghai Jim he would have reported that many minutes of Ballard in his little G Block room were filmed, and perhaps the most personally emotional moments of the trip are revealed there. (3) If a person’s basic personality is fixed by age seven (Seven Up, etc), then Baxter misses the boat on JG growing up on Amherst Ave, and doesn’t get Lunghua, either. I’ve talked with three people who were at Lunghua, and one of them remembers JGB as an outrageous story-teller in the camp, although her memory may have flipped and she’s also remembering the movie/book of Empire. Regardless, JG’s youth is a history only JG has revealed, and given they're all gone it looks like we’ll never really know how he was psychologically formed, or whether or not he was a petulant, lonely, overdressed, clever kid keenly aware of the adult world. Is a picture worth a thousand words? The confident, fat-faced kid balancing on his bike looking at us from the cover of Miracles of Life says a lot, as I don’t see any parental fists encouraging that Mona Lisa smile. That this is all lost now is something JG himself appreciated. As he told me in 2007, “In an odd way it’s quite reassuring that everything has changed so much — the Shanghai I knew, along with 31 Amherst Avenue and Lunghua camp, only survive inside my head”, and, apparently, Baxter’s imagination, as he uses JG’s 1991 return to Lunghua for a BBC documentary -- Shanghai Jim -- as an opportunity to show JG’s allegedly psychopathic response to his room — “I entered puberty here” -- as all he has to say. So much emotional complexity, so much information, swept aside by Baxter. In actuality, if Baxter had really watched all of Shanghai Jim he would have reported that many minutes of Ballard in his little G Block room were filmed, and perhaps the most personally emotional moments of the trip are revealed there.(4) A lot of the nasty innuendo is Baxter’s attempt at foreshadowing. He drops a few insinuations, then jumps to the next chapter and a return to the chronological approach. It’s supposed to keep us glued to the page even if the stuff we’re reading to get there is drivel. His readings of the works seem undergraduate in sophistication, involving a lot of searching for sources, real & imaginary, then an extensive plot summary with commentary, and finally some reaction, usually negative, and often associated with media reviews and book sales reports. Rarely a word on style, which, one has to admit, is JG’s greatest talent. Is his prose like ad copy? Only in rhythm. Nor does Baxter apply any Freudian analysis to the stories, but in a Ballardian reversal, applies Freud to JGB! And even then he doesn’t bother to examine JG against the pretty damn obvious oedipal complex, repetition, lifelong interest in how the id manifests itself in civilization, death instinct, repression... yadda yadda. (5) Baxter’s not very good analysing the novels, either, but it’s fun to watch him wallow around, especially on novels we’ve studied. He also seems to have steadfastly ignored the critical canon, as there’s no quotes from Luckhurst, Gasiorek, Jeannette Baxter... even the approachable Peter Brigg is ignored. He also doesn’t seem to grasp elective psychopathy, either. Misses it in High-Rise and Kingdom Come, and he also misses the fact in Kingdom Come the ending is unlike any other Ballard ending – the hero actually gets the girl -- surely that’s a sign of finality, no? (6) What action or inaction might Ballard have committed to goad Baxter into writing such an obviously biased account? Ultimately, I think we must realize Baxter was a less-successful writer than Ballard, and recognize this book encapsulates a certain amount of professional jealousy. This so-called biography has more holes in it than the Albert Hall, none the larger than Baxter’s book-long fantasy that Ballard was both a psychopath and some kind of prescient adman who spent his entire career burnishing his reputation through constant re-writes. The other joke is, as an unauthorized bio, Baxter was not given access to the papers and people who could tell him the real story, so he is forced to utilize Ballard as a source, even though he claims that source is untrustworthy! This is an amateurish hodge-podge, with no footnotes and a very weak index. Enough. |

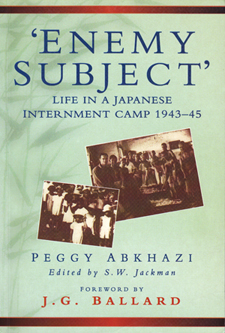

|||