|

|

||

|

||

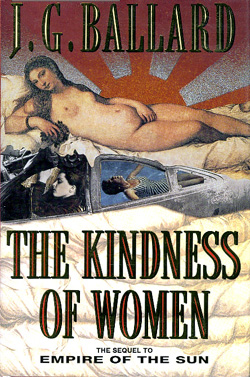

From JGB NEWS, Number 20, August 1993 Fact and Fiction in JG Ballard's The Kindness of Women By David Pringle A very preliminary reading, with comments on the novel's status as a "sequel" to Empire of the Sun. (Page references are to the recent paperback editions of Empire of the Sun and The Kindness of Women, both published by HarperCollins/Grafton, 1992.) Chapter One: Bloody Saturday August 1937, Shanghai. Young Jim, described as "a 7-year-old," witnesses the bomb explosion which kills over 1,000 people at the Great World Amusement Park on the Avenue Edward VII. We are also introduced to Olga Ulianova, "my white Russian govern-ess," and to young David Hunter, "a friend who lived at the western end of Amherst Avenue."  The Great World Exhibition Grounds, Shanghai, 1937. Yes, those are bodies on the ground; over 200 civilians were killed. This is fiction based on a factual background. Such a bomb did fall on Shanghai; it's also referred to in Empire of the Sun (page 25). However, it's extremely unlikely that the young Ballard actually saw the event with his own eyes. Born 15th November 1930, at the time of the bombing he would have been six years and nine months old; I find it hard to believe he was cycling around downtown Shanghai at that tender age. In the first of many time-shifts which mark the novel, Ballard has super-imposed his later cycle-rides (probably undertaken when he was ten or so) on the events of August 1937.  JGB in 1936. Too young to bike, but not too old to ride. Neither Olga, the Russian girl who is Jim's governess, nor David Hunter, his young friend, was mentioned in Empire of the Sun, so the characters and events of the later novel already seem to be taking on a separate, "parallel" existence. (The governess in the earlier book was called Vera Frankel, and Jim's "closest friend" was Patrick Maxted; of course, the real-life Jim may have had several governesses and many friends over the years of his childhood.) Chapter Two: Escape Attempts November 1943, Lunghua camp. While some youths try to escape from the camp, 13-year-old Jim attempts to raid the food store with the help of a broken bayonet -- in effect, burrowing his way further into the camp. Characters mentioned, besides David Hunter (who will recur throughout the book), include Mr Hiyashi (the camp commandant), Peggy Gardner ("a tall, 14-year-old English girl"), Mrs Dwight, Dr Sinclair, Mr Sangster, Mrs Tootle, Mr Christie, Mariner and the Ralston brothers.  Lunghwa Civilian Assembly Centre, Shanghai. The Japanese interned nearly 2,000 people under brutal conditions from 1943 to 1945. Again, fiction based on a factual background. This is another portrayal of daily life in Lunghua, where the real-life Ballard was interned from 1943 to 1945; however, there is little reason to suppose that most of the incidents are actually "true." None of the characters listed above was mentioned in Empire of the Sun (where the camp commandant was called Mr Sekura), giving this chapter the feel of a variant "take" on the camp experience. There are, however, passing mentions of Private Kimura and Sergeant Nagata, the Americans Basie and Demarest, and Mr and Mrs Vincent, characters who did appear in the earlier novel -- although none of them plays any significant part here. Chapter Three: The Japanese Soldiers August 1945, Lunghua and Shanghai. After the guards finally disappear, Jim leaves the camp and walks back to Shanghai along a railway line. At a station on the way he encounters a group of Japanese soldiers who are slowly strangling a Chinese captive. Reaching home, Jim is reunited with his parents. There are further encounters with Peggy Gardner, David Hunter and Olga Ulianova before Jim sets sail for England with his mother aboard the R.M.S. Arawa. As the ship passes Woosung he sees a beached tank-landing craft crammed with Japanese prisoners of war, and there is a hint that terrible carnage is about to take place.  The R.M.S. Arawa, once a ritzy ocean liner from New Zealand . Much of this is probably factual. The event he witnessed at the railway station was clearly traumatic for Ballard, and he first mentioned it in print in his afterword to the story "End-Game" (in the anthology Backdrop of Stars, edited by Harry Harrison, 1968): "Three weeks after the war ended I walked back to the camp along the Shanghai-Nanking railway line. At the small wayside station an abandoned platoon of Japanese soldiers were squatting on the platform, watching one of their number string up a Chinese youth with telephone wire."  Something very like the later incident of the captured Japanese troops in the landing craft was also touched on in his story "Tolerances of the Human Face" (1969; admittedly, in a fictional context, though the description there has the ring of plain truth): "... The Japanese soldiers in the cargo well were in a bad condition. Many were lying down, unable to move..."  Americans transporting Japanese prisoners to Japan, 600 to 700 at a time. This third chapter also marks a radical break with the events of Empire of the Sun. In the earlier novel, the camp's inmates were sent on a forced march northwards, with many of them dying on the way, but (as in real life) this appears not to have happened to the Lunghua prisoners in The Kindness of Women. Plainly, this chapter of the latter novel is a variation on the events and themes of the previous book, not a direct sequel. Chapter Four: The Queen of the Night 1950, Cambridge. Jim is a medical student, carrying out anatomy-class dissections of a female cadaver. We meet Peggy Gardner again, and two important new characters appear: the "quick-witted schoolgirl" called Miriam, and the psychologist Dr Richard Sutherland. Soon, Jim and Miriam become lovers.  JGB in a double-exposed self-portrait, Cambridge, 1950. Fiction based on fact. Ballard memorably described his undergraduate experience of anatomy in a 1970 Penthouse interview with Lynn Barber: "To see a cadaver on a dissecting table and begin to dissect it myself and to find at the end of term that there was nothing left except a sort of heap of gristle and a clutch of bones with a label bearing some dead doctor's name -- that was a tremendous experience of the lack of integrity of the flesh, and of the integrity of this dead doctor's spirit." There was no suggestion, however, that the "dead doctor" in question was female. The real-life model for Peggy Gardner is unknown to me; possibly there's a touch of Ballard's sister in her (though his sister is seven years younger than JGB), but the character of Miriam is obviously based on Ballard's wife-to-be, Helen Mary Matthews ("a great-niece of Cecil Rhodes," according to the biographical blurb in the Penguin edition of The Drowned World, 1965). While it is quite possible that they met at Cambridge, I don't know whether they met as early as 1950. The character of Dick Sutherland is largely based on Ballard's friend, the late Dr Christopher Evans (as becomes evident later in the book), but I doubt that in reality they met before the 1960s. Chapter Five: The NATO Boys 1954, Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan. Jim and David Hunter are trainee pilots in the RAF, stationed in Canada. On a solo flight, Jim spots a crashed aircraft lying on a lake-bottom, and later he suffers a near-crash himself. He and David also share in sexual adventures with local prostitutes.  More fiction based on fact. Ballard did serve in the RAF, in Canada, but left after a short time; whether he ever reached the stage of solo flight, and whether the incident of the crashed plane has any basis in fact, I don't know. This is an appropriate point to state that I believe the recurring character of David Hunter to be almost completely fictional. He may be based in small ways on a number of people, but clearly his role in the novel is to act as a dark alter ego to Jim, the narrator. He represents the wild side of Ballard's own character, the man who goes out and does various things that the narrator fantasizes about. He also serves as an agent to bind together the disparate parts of this very episodic book. Chapter Six: Magic World 1959, Shepperton. Jim and Miriam have been married for some years, and she is now expecting their third child. A domestic idyll unfolds as Jim plays with his son and daughter, Henry and Alice, and as he makes love to his wife. The new baby is born: "Waking into the deep dream of life, it seemed not young but infinitely old, millions of years entrained in the pharaoh-like smoothness of its cheeks..." (Compare a passing description of a newborn child in Ballard's 1969 review of "The Voices of Time", ed. J. T. Frazer, New Worlds no. 186: "lying between his mother's legs, older than pharaoh...")  This charming chapter must be almost entirely factual, although the chronology is distorted. According to many statements in JGB's interviews, the Ballard family actually moved to Shepperton in 1960, after the birth of their third baby (daughter Beatrice) in 1959. In the novel there is a reference to Jim and Miriam having watched part of the filming of Genevieve at Shepperton, but that film was made in 1953, seven years before the real-life Ballards arrived in the town. Chapter Seven: The Island Summer 1964, Costa Brava, Spain. Jim, Miriam and family are holidaying in the sun. They lounge on the beach, swim, explore a small island, and make a number of new friends. These include Peter Lykiard, an English lecturer, and Sally Mumford, an American student who has come to Europe "to meet the Beatles." The chapter ends, shockingly, with Miriam's death after injuring her head in a fall.  Mary Ballard, 1954 Fiction based on fact. Ballard's wife Mary did die in Spain in 1964; however, the cause of her death was an infection, not an injury. "My wife died from galloping pneumonia," as Ballard stated in his 1983 postal interview with Thomas Frick (later published in a shorter version in Paris Review), "but... no violence or car crashes, which many people imagine." Presumably, in the novel he has changed the circumstances slightly in order to make the event seem more dramatic and sudden. Chapter Eight: The Kindness of Women 1964-65, Shepperton. In the aftermath of Miriam's death, Jim decides to remain in the same house and to keep the children with him. In a tender scene, he makes love to Miriam's older sister, Dorothy. A year passes, during which he is celibate. One has to assume that most of this moving chapter is fundamentally true; though whether "Dorothy" had a real-life counterpart we cannot know. Chapter Nine: Craze People Circa 1967, Shepperton and elsewhere. The American girl, Sally Mumford, comes on the scene again, befriending Jim and the children. Around them, Swinging London and the 1960s "counter-culture" are now in full bloom. Jim, the children, Sally and Peter Lykiard attend an open-air pop concert near Brighton. Later, Jim and Sally make love. He introduces her to Dr Dick Sutherland who has by now become a television pundit.  Undoubtedly much of this chapter is based on actual events, though it and the following three chapters are somewhat confusing in their chronology. The pop concert which is the model for the one depicted here was called "Phun City," and actually took place near Worthing in 1970 -- with Ballard, William S. Burroughs and other writers in attendance (see Paul Ableman's rather sour allusion to it in his review of Hello America, 1981). Charles Platt, in his review of The Kindness of Women (in the New York Review of SF, 1992), has hypothesized that the character of Sally Mumford is based in part on the novelist Emma Tennant -- a claim about which I can make no comment other than to point out that there are obviously huge differences between the character as depicted and the real-life Ms Tennant. Chapter Ten: The Kingdom of Light June 1967, Shepperton. Dick Sutherland gives Jim some LSD and he experiences a bad trip, at one point feeling the urge to walk on the river. There is another visit from the motherly Peggy Gardner, and we also meet Jim's new friend Cleo Churchill.  Homage to Claire Churchill, 1967 Such an LSD experience did occur in 1967, just once, according to Ballard's testimonial in various interviews -- although he didn't go so far as to try to walk on the water (see the interview with Stan Nicholls in Blast, 1991). Some of Dick Sutherland's psychological patter in this chapter is nearly identical to remarks that Ballard himself has made in a number of interviews. Apart from Miriam/Mary, the character of Cleo Churchill is the most transparent in the book: she is obviously based on JGB's close friend Claire (publicly referred to by Ballard in "Homage to Claire Churchill," the first of his Advertiser's Announcements, in Ambit and New Worlds, 1967). Chapter Eleven: The Exhibition 1969, London and Shepperton. Sally Mumford and David Hunter reappear, the former now on hard drugs and the latter indulging an obsession with road accidents. Jim mounts a four-week exhibition of crashed cars at the Arts Laboratory in London. Driving home after the exhibition's close, he suffers a serious car crash and is slightly injured.  Carhenge, Nevada, by starlight. Fiction with some small basis in fact. In this, perhaps the least convincing chapter in the novel, David Hunter has been reimagined in the role of "Vaughan" from the novel Crash -- pure fiction, one hopes, and rather unnecessary given that that book already exists and deals with the same material more powerfully. The "Crashed Cars" exhibition really took place, although it did so in April 1970 (see advert in New Worlds 200) -- not a year earlier as seems to be suggested in the novel. Ballard's own car accident also occurred, although not until much later, in 1972 (shortly after he had finished writing Crash). Chapter Twelve: In the Camera Lens 1969, Rio de Janeiro. Jim and Dick Sutherland attend a film festival in Rio, where they have brief meetings with famous people. They also have encounters with local prostitutes.  Brian Aldiss, Harry Harrison, Mrs Sheckley and JG Ballard between screenings at the Second International Film Festival, held in Rio de Janeiro, March 23-31, 1969. Fiction based on fact. There was a such a festival in Brazil in 1969 (devoted to science fiction), and Ballard was invited to give a speech. Brian Aldiss, Frederik Pohl, Harlan Ellison, Poul Anderson and other well known sf writers were also present. Whether Christopher Evans (Dick Sutherland's real-life model) accompanied Ballard, and whether any of the other events are true, I don't know but I rather doubt. Just possibly, the character of Dick Sutherland is here based -- in part -- on JGB's recollections of his friend and fellow-writer Brian Aldiss. (Having attended in 1985 a smaller-scale but not dissimilar event where Brian and I were guest speakers, in Nice, south of France, I know that he can be lively and sometimes outrageous company.) Chapter Thirteen: The Casualty Station Circa 1972, London area. Jim visits David Hunter in a mental hospital where he has been institutionalized after a deliberate car-smash. There are further references to the progress through life of Sally Mumford (attempting to kick her drug addiction) and Richard Sutherland (a success on television). Jim also visits Peggy Gardner in her "small Chelsea house" and makes love to her for the first time. No particular comment to make on any of this, other than to reiterate that David Hunter is largely a fictional character; however, the details of the visit to the mental institution are probably based on a genuine experience which Ballard has alluded to in the 1990 notes for the Re/Search Atrocity Exhibition. Chapter Fourteen: Into the Daylight 1978, Shepperton and Norfolk. Jim visits Sally Mumford and her new family near Norwich, passing through Cambridge en route. David Hunter joins them, and they witness the excavation of the remains of a Battle-of-Britain Spitfire. This is probably based on memories of an actual visit to that part of England. The excavation of the aircraft obviously reminds us of Ballard's story "My Dream of Flying to Wake Island" -- perhaps based on the same experience -- but that story was published in 1974, well before the supposed date of the events in this chapter. Chapter Fifteen: The Final Programme Autumn 1979, London and Shepperton. Dick Sutherland, dying of thyroid cancer, makes his last television documentary -- a study of his own illness and death -- which Jim encourages with some misgivings.   American edition of Dr Evans' book. A moving chapter which is a fictionalized version of the death from cancer of Dr Christopher Evans. In actuality, his final TV programme was a series on the future of computing entitled The Mighty Micro (also the title of a book he had published in September 1979) and it was broadcast shortly after his death. (I had the privilege of meeting him myself a couple of months before his death, at the World SF Con in Brighton.) Chapter Sixteen: The Impossible Palace 1980, Shepperton and Runnymede. Musing on Dick's death and on the departure of his grown-up children, Jim visits a funfair in Shepperton. Later, he makes love to Cleo, and the two visit Runnymede where they witness a near-fatal accident by the riverside when a car rolls into the water. The child in the car is revived by a mysterious hiker. A wonderful, quiet chapter, suffused with some of the spirit of The Unlimited Dream Company (1979), and almost certainly based on real-life incidents. Chapter Seventeen: Dream's Ransom 1987, Surrey and Hollywood. Jim participates in the filming at Sunningdale of a movie based on one of his novels. Later, he and Cleo fly to California for the film's premiere. There, Jim encounters once more Olga, the Russian woman who was his governess in Shanghai, and they make love.  All the movie business is of course closely based on the filming of Steven Spielberg's version of Empire of the Sun (though neither director nor title is named in the book), the Hollywood premiere of which Ballard attended in December 1987. The meeting with Olga is surely fictional and is added to provide the novel with an appropriate feeling of closure. Most of the above conjectures are highly speculative -- but given the "semi-autobiographical" nature of the novel people are going to make such speculations, now and later. I offer this as a possibly useful piece of spadework, no more. (DP) Reply from JG Ballard: 13th October 1993 Dear David: Many thanks for JGB News 20, as always full of fascinating material more or less new to me. I admire your expert detective work into Kindness of Women -- you're pretty well absolutely accurate. I've always stressed that both Empire and Kindness of Women were novels, though based on my own life without which they could never have been written at all. They represent my own life seen through the body of fiction that was prompted by that life. Most of the characters in Kindness of Women are complete inventions. Sally Mumford, Peggy Gardner and David Hunter are wholly imaginary, and Sally is not drawn in any way from Emma Tennant, though there were lots of scatty young women like her in London in the 60s. Hiyashi was the real name of the Lunghua commandant, a former diplomat who was moved by the Japanese military when they took over the camp in the last much tougher year of the war. (By which I mean they kicked Hiyashi out and put one of their officers in charge -- the Japanese army had run Lunghua and all the other camps from the start.) Curiously, after the war my father travelled down to Hong Kong to speak in Hiyashi's defence at the war crimes trials there, and he was rightly acquitted. JG Ballard, Shepperton Reprinted with permission. Contents © Copyright David Pringle 1993 Fessin Up Time: All the pix of JGB and his family I brazenly scanned from the invaluable text, JG Ballard (Re/Search 8/9). |

||