|

|

||

|

||

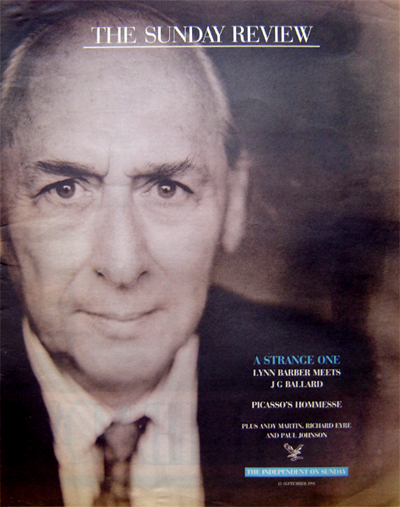

Alien At Home The Lynn Barber Interview What happened to the boy Jim after the Japanese left Shanghai? J G Ballard waited seven years to write a sequel to Empire of the Sun, and now those who thought they knew him may find they don’t. J G Ballard was 54 and had published 17 books before he finally got around to writing about his own life. The first 17 were all science fiction; the 18th -- Empire of the Sun, a world bestseller -- described his childhood in Shanghai and in particular the three years, aged 12 to 15, he spent in a Japanese internment camp during the Second World War. Anyone who read the book or saw Steven Spielberg's film must have wondered: what happened then? How did the boy Jim, who experienced such extraordinary, terrifying adventures, who was starved and bombed and saw adults torturing each other, develop into the writer J G Ballard? Frustratingly, Ballard's next novel, The Day of Creation, failed to answer the question because it was a return to his pre-Empire science fiction style. For seven years it seemed that Empire was the only glimpse of autobiography we would get. But now he has filled in the rest of the story in The Kindness of Women, which more than justifies the long wait. This time, surely, he will win the Booker prize. “People who've never met me,” he remarks, “come here expecting to find a Burroughs-like figure in a miasma of drugs-taking and child-molesting, and are amazed by the rather bourgeois character they find.” Well, up to a point, Jim. I have known him since the Sixties and, as always, it is a deeply unhinging experience to walk down the quiet suburban Shepperton street and squeeze past the car in his front garden, to knock at the peeling door of his tiny, ordinary, grotty Thirties semi and find the great mad-staring-eyed Jim inside. It is as if you had opened the hamster cage and encountered a mountain gorilla. At 61, he is not quite as fast-talking and booming-voiced as he once was, but he is not exactly quiet either. “Alcohol?” he shouts (it is 11am), “or soda?” These are the only beverages in the house. He has lived here for 30 years and apparently never cleaned it. The kitchen still features its teetering stacks of gungy saucepans and rows of empty whisky bottles. The two sitting-rooms in their pall of dust are rendered even tinier by two vast Surrealist paintings he commissioned with the fruits of his Empire royalties -- copies of works by Paul Delvaux that were destroyed in the war and survived only in photographs. His other gesture to interior decoration -- a large silver foil palm tree -- has been banished upstairs. His old favourite book, Jacob Kulowski's Crash Injuries, is still on the shelves. When I first knew him in the Sixties, he was a familiar, but jolly peculiar, figure on the New Worlds (sci-fi magazine) or Arts Lab scene. He was older than most -- thirtysomething rather than twentysomething -- and rather obviously public-schooly and ex-RAF, whereas the other sci-fi writers were all beard-and-sandals brigade. He drank whisky while everyone else smoked pot, and often turned up with startlingly famous friends, such as Lucien Freud and Francis Bacon and Eduardo Paolozzi. (Freud did a very good portrait of him.) He was completely obsessed with car crashes, and with John F Kennedy's assassination, of which he could recite every detail. He organised an exhibition of car crashes at the ICA and raved happily about the erotic conjunctions of mangled metal and flesh. He could and sometimes did silence whole dinner parties by suddenly producing photographs of his girlfriend's car-crash injuries, or urging her to show off her scars. So, while he looked cuddly and avuncular, there was also a sinister, or straightforwardly mad, side of which one was wary. I thought at the time that I knew him quite well, but I realise now, having read The Kindness of Women, that I knew him hardly at all. The Kindness of Women begins with a brief account of his childhood in Shanghai and carries on to the present day. As soon as he was liberated from the Shanghai camp, he was sent back to England, to the Leys School. He had never lived in England before and found the class system baffling -– “I could see why a gentleman shouldn't wear a red suit, but I couldn't understand why he shouldn't wear brown.” Also, it all seemed incredibly tame after Shanghai. He went to Cambridge to read medicine, intending to be a psychiatrist (“for the obvious reason -- ie, ‘Physician, cure thyself’. Not that I was ever neurotic, but …”). He left after two years, realising that if he went on with medicine he would never have time to do any writing and “I felt the pressure of imagination against the doors of my mind was so great they were going to burst anyway.” He went on writing while training as a pilot in Canada, working as an encyclopaedia salesman and on a technical scientific magazine. In 1960, he published his first novel, The Drowned World, to huge acclaim, and became a full-time writer, which he has been ever since. He married, bought the little house in Shepperton where he still lives, and had three children. In 1964, when his children were four, five and seven, his wife died suddenly during a holiday in Spain. He raised the children himself without any help (“You can do all the housework in five minutes if you don't make a fetish of it”) and thoroughly enjoyed it. He never re-married, though he has a longstanding girlfriend called Claire to whom he proposes periodically. This is all good material, but what makes The Kindness of Women special is its depiction of man-woman relations. It is the first time he has tackled the subject. Empire -- his other realistic novel -- was about boyhood. His science fiction books had women in them, but they were, as he says, “like figures from Surrealist landscapes” -- ie, emblems rather than flesh and blood. I assumed he was probably a bit kinky and liked to have women dressed in rubber or astride motorbikes or something. How wrong I was. Kindness is the most convincing account I have ever read of sweet, ordinary, fallible, domestic relationships. As he says, “That title is not an accident. I've always been lucky enough to be able to rely on the kindness of women, and they've been a tremendous source of richness in my life. I'm not a clubby man; I've always vastly preferred the company of women. I actually like women, unlike most Englishmen. One of the benefits of my camp upbringing was that I was in very close contact, practically 24 hours a day, with a lot of girls my age who had to fight for survival too, so I always saw them as equals.” The cover blurb on The Kindness of Women describes it as a “hybrid of autobiography and novel”. It reads like straight autobiography. Jim, on the other hand, is keen to insist it is fiction. “Christ!” he exclaims, “I couldn't publish the book if I said it was the truth!” Nevertheless he admits: “It's psychologically wholly true. It's literally true half the time, and psychologically true the whole of the time.” Interesting, therefore, to see where his psychological truth has veered from reality. I know of two instances, though there are probably more. First, his wife's death. She died very suddenly on holiday in Spain (as in the novel), but of galloping pneumonia, not from a fall. Why the alteration? “I just couldn't have faced writing it exactly. I don't think I ever would want to. I mean the way I describe it was just as terrible, but at least it was quicker -- death from that sort of pneumonia isn't nice.” The second instance is more mysterious. Both in Empire of the Sun and The Kindness of Women, he describes the boy Jim as being separated from his parents in the chaos of the Japanese invasion, and sent to a different camp, so that he is effectively orphaned for the three years of his internment. This gives his situation a terrible poignancy -- in Kindness, for instance, he keeps trying to attach himself to different families and is always rebuffed. But the real Jim was with his parents (and his sister) all the time, living together in one tiny room. This is not a detail: it changes the psychological colour of the situation completely. Why didn't he include his parents? “I don't know. I think in a sense it was psychologically truer to present myself as alone … There was a separation between me and my parents in the camp -- even though I was living with them for three years in a room half the size of this. The camp was like a huge tenement family -- a huge slum -- and it just fed my imagination in a thousand-and-one little ways. And I think my parents simply couldn't match this input of personalities and adventures, and I spent all my time hanging around with other adults. “I was incredibly hyperactive and demanding. I used to exhaust everybody -- because there were a lot of well-educated people in the camp -- and I was forever wanting to know how you built a suspension bridge, or what was the explanation for this chess move? I was insatiably curious. And there were all these American merchant sailors in the camp, and I loved them. They had cowboy belts and fancy kitschy pens, all the things I adored, and old copies of Reader's Digest and Popular Mechanics -- I'd run errands, do anything, to get my hands on them. I just loved everything American -- still do, actually. And I'd never really been allowed to meet any working-class people in pre-war Shanghai, and then I met them and found they have a colossal vitality because they're not repressed like the British middle class. And you see, in a place like an internment camp, parents have none of the levers with which they can control their children, particularly teenage boys. My mother once described me years later as a free spirit -- and I think I was.” Did his parents suffer much more than he did in the camp? “I think so, yes. I had a good time. I thoroughly enjoyed myself. Except towards the end, when food supplies collapsed and we were living on warehouse scrapings. We used to push the weevils to the side of our plate, but the day came when my father said, ‘We've got to eat these weevils because they contain protein’ -- which we did. But children can put up with all that. They don't even notice it. So I had a good time, but my parents had much harsher memories of the camp …” This is all he will say about his parents, and when I persist, he holds up his hand, “Please! Remember this book is not just about Shanghai.” Yes -- but it is striking how often he, not me, leads the conversation back there. And in Kindness it is the thread that holds the whole novel together. It had, and retains, a glamour for him that nowhere else has ever matched. “If I'd gone on living in Shanghai, I probably would have absorbed it all, but I left at this sudden, dramatic moment, which meant that it remained extremely vivid. There are certain kinds of dramatic experience, whether for good or bad, that one never completely digests; they go on reverberating through one's life for ever. And I arrived in England with a huge undeclared cargo, an unfinished agenda, and that's why in Kindness I felt I had to make sense of it, of everything.” This summer he returned to Shanghai for the first time, to make a BBC Bookmark programme. He found it strange. “Shanghai itself is strange because it's all so well-preserved -- art deco and port-hole windows and ocean liner balconies, the lot. We found my old house -- it's now an electronics library but like a museum of bathrooms, with all five bathrooms intact but sans plumbing -- and we found the camp and even the actual room we lived in for three years. It's now a high school. “I was expecting a tremendous jolt, but in fact, even standing in my old bedroom, even in our little room in the camp, I didn't feel a great rush of memories pouring in because the memories were all there. I'd remembered it perfectly. It was as if I was going back after three weeks, not half a century. I felt tremendously elated. Funny, that. I still do, actually. I felt as light-headed as if I'd had three double gins. I think it was because all my memories had been confirmed. “There was a terrible danger in going back. I thought: all these memories which had sus-tained me for half a century, which kept me going during the dark days, and fuelled my imagination … what if I go back and my whole dream of Shanghai was an illusion - what then? I was frightened that no new memories would be evoked but I would have erased the old ones. But, in fact, just the opposite happened: it was even richer than I remembered.” The great question anyone who knows Ballard's work must ask is: why didn't he write Empire of the Sun and The Kindness of Women years earlier? Most novelists begin by writing about their own experiences and become less autobiographical as they go on. But Ballard wrote for a quarter of a century before mining his memories. It is tempting to see all his earlier fiction as a kind of displacement activity, a putting-off of the day when he must face his own past. He has sometimes admitted that he wishes he wrote Empire of the Sun earlier, but mainly because it might have won him a bigger audience for what he considers his more important “apocalyptic” novels (he dislikes the term science fiction). Empire made more money than all his other novels put together, but the others have all been published in at least 20 lan-guages, and are perhaps better-known in Japan, Italy, France and Spain than they are here. At least three of them -- The Drowned World, The Drought and Crash -- are generally considered classics. Crash (1973) was the most controversial, dealing as it did with “the mysterious eroticism of wounds; the perverse logic of blood-soaked instrument panels, seat-belts smeared with excrement, sun-visors lined with brain tissue”. The publisher's reader who first saw the manuscript -- herself the wife of a psychiatrist -- wrote: “This author is beyond psychiatric help.” But he is probably right to call it his most fully realised achievement. “I mean, a book like Crash was a much bigger challenge to me, morally and imaginatively, than Empire, which life just handed to me on a plate. There I was with these small children crossing the road 10 times a day while I was immersing myself in this psychotic world of car crashes. Nature could have played a very nasty trick on me.” Was there a degree to which Crash and the other “atrocity” novels of the Seventies were an attempt to come to terms with his wife's death? “Yes, I think that's fair. You can't face the unfaceable: you just turn away. So all that anger and grief was displaced. The books that I wrote in the late Sixties and early Seventies are filled with this desperate anger, this attempt to make sense of what seemed to me a meaningless cruelty at large in the world, to assuage this terrible sorrow. In a way I merged my wife's meaningless death with the meaningless death of Kennedy and all the other meaningless deaths -- in car crashes, in Vietnam -- that you saw on TV. And I felt a tremendous resentment and a certain amount of guilt. Not that I was to blame for her death, but they say you can judge a man by the state of his wife's health, and my wife was dead. I felt that Nature had committed a terrible crime against this young woman. I feel that now. I just couldn't find any explanation. I think now, looking back on these events, a sort of calm resignation is about all one can muster -- which is a terrible thing to say.” Those “apocalyptic” novels, he thinks, are now behind him. He is still curiously waiting to see what he will write next, and is not even sure that he will write anything at all: “If no obsession surfaces, I'll simply call it a day.” But he thinks if he does write more, it will be a continuation of his new realistic mode. “Oddly enough, as you near the end of life, you begin to treasure the commonplace and ordinary in a way that you don't in your twenties and thirties. I mean, the play of light on a windowsill -- since it may be the last one that you see, you treasure it. And you treasure the intimacies of ordinary human relationships which you take for granted when you're younger.” “Look, Lynn,” he suddenly says, with considerable urgency, “what you've got to convey in this interview is that this is a man of complete and serene ordinariness. I'm not a literary man, that's the important thing, and I'm not a commercial writer either. I'm really a kind of naive, a perpetual innocent, not far removed from the village bumpkin who still hasn't worked out what a set of traffic lights is.” This is true in parts. It is true that he is not a literary man -- he never sits on panels, never goes to literary conferences, never gives lectures on whither-the-novel, and in fact hardly reads any novels -- he is still unacquainted with the works of Martin Amis and Julian Barnes. (His literary education stops at Greene, Burgess, Burroughs and Genet.) He used to know some other writers -- Michael Moorcock, Angela Carter, Emma Tennant -- but nowadays he says he rarely goes out. “I have become a bit of a recluse.” However, it is absolutely not true that he is “a man of complete and serene ordinariness”. Indeed, what he thinks of as his ordinariness -- his life in Shepperton -- is actually extremely odd. "Thousands of families live in houses like this,” he says defensively, which is no doubt true, but I am sure that most of them would have dusted them occasionally, or painted the walls, or renewed the lino, or removed the rows of empty whisky bottles from the kitchen. It is as if J G Ballard entered an ordinary house in about 1950 and said, “I’ll have one like this” and never touched it again. I always assumed he lived like this because he was poor. But then he made at least half a million from Empire of the Sun and went on living just the same. Anyway, it turns out he wasn't really poor at all. He told me that after he became a full-time professional writer in 1960 his income remained exactly the same as that of a suburban GP -- until Empire, when it suddenly shot up to that of an American GP. But a suburban GP would never live in a house as grotty as his. He admits this is a puzzle. “Yes, I never understood that. Doctors live in far greater style. Maybe I was spending too much on alcohol! But it's not possible to spend a very great deal on alcohol -- I mean a bottle of whisky a day is only three thousand pounds a year; it's not like gambling or women.” Pause for a brisk detour round his drinking habits. When he was bringing up the children, he says, he had his first drink of the day as soon as he'd delivered them to school, ie, at 9 am, and carried on from there. “I was never drunk, but I would have a glow all through the day.” He felt he had too much energy and that drinking helped to curb it. But then in middle age, he started cutting back: “It was a great achievement when my first drink of the day was at noon and then -- it was like the Battle of Stalingrad -- six and now eight. Life is much duller as a result.” But to get back to his life style: even assuming he bathes in whisky, it still doesn't explain why he lives as modestly as he does. Is he very mean, and keeps it under the mattress? Or is he very generous, and gives it all away? Or does he have a completely different home somewhere, and only use Shepperton for receiving journalists? This seems quite a tempting theory -- except that he is always in when you ring the Shepperton number. He finds my persistence with the subject at first funny and then irritating: “You're saying, why haven't I moved my life into a much more glamorous phase? Would it satisfy you if I moved to a typical piece of Twenties stockbroker Tudor in Chertsey and furnished it all from Harrods? You'd like that, would you?” No, but … “Living in this house is a political statement. I'm identifying myself with a social class that stands outside the self-strangulating, taboo-ridden world of the English middle classes. Put that in your article: build it up a bit.” And then, as I laugh merrily at what I take to be a joke, “I mean it.” The truth is, he doesn't particularly care where he lives, because he lives inside his head. He would quite like to live in Roquebrune, in the South of France, where he goes every summer for his holidays, and will do so one day when his girlfriend retires. But meanwhile Shepperton is as good as anywhere. He likes the fact that many of its inhabitants work at the film studios or Heathrow; he likes the used-car lots, the Thirties Modernist buildings that remind him of air traffic control towers, and the proximity of the motorways -- not for convenience, because he rarely travels anywhere, but because he admires their architecture. He finds Shepperton “American” and there is no higher compliment in his book. And because he brought his children up in Shepperton, the house, the streets, the park, the river bank, are filled with happy memories. When I was leaving, he asked me, “How many of the people you interview do you envy?” “Not many. You more than most.” “What?” he laughed. “Living in a house like this!” No… there is nothing enviable about his material circumstances. But there is something extremely enviable about his indifference to them. “There are people,” he says cheerfully, “who are constantly rediscovering the world on a second-by-second basis, for whom every minute is a new excitement. Whether it's a sort of naivete or not I don't know, but I've always been one of those. I wake up in the morning and look out at Shepperton and I'm always always amazed and think, What is this?” |

||