|

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

What are we to make of J.G. Ballard’s Apocalypse?

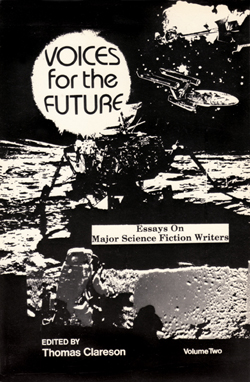

By H. Bruce Franklin  More than any other writer, J. G. Ballard incarnates the apocalyptic imagination running riot in Anglo-American culture today. Ballard began projecting multiform visions of the end of the world in the late 1950s, even before these became the rage, and he has been consistently, in fact obsessively, at it every since. Along with other British and, somewhat later, American purveyors of literary gloom and doom, Ballard has been a symbol of the ascendancy of the "New Wave" in science fiction. And the "New Wave" has been a leading force in the broad and deep expansion of a doomsday mentality in our culture. More than any other writer, J. G. Ballard incarnates the apocalyptic imagination running riot in Anglo-American culture today. Ballard began projecting multiform visions of the end of the world in the late 1950s, even before these became the rage, and he has been consistently, in fact obsessively, at it every since. Along with other British and, somewhat later, American purveyors of literary gloom and doom, Ballard has been a symbol of the ascendancy of the "New Wave" in science fiction. And the "New Wave" has been a leading force in the broad and deep expansion of a doomsday mentality in our culture.From the beginning of the twentieth century until shortly before World War Two, there was a widespread belief, especially in England, the United States, and Germany, that explosive technological advances were about to cause a tremendous leap in progress for mankind, and the scientific-technical elite were the living embodiment of this creative potential. Obviously the one and only form of literary art congenial to such a vision was science fiction. Hence the creation of the mode of science fiction dominant in the first half of our century, personified by H. G. Wells in his "optimist" period (from The Food of the Gods in 1904 and A Modern Utopia in 1905 through The Shape of Things to Come in 19341); Hugo Gernsback and his creation of technocratic science fiction as an autonomous, self-conscious genre; and German science fiction, with its theories of scientific genius, racial supermen, genetic purification, technological marvels, super-weapons, and world empire, all central to the emerging Nazi ideology.2 Today -- that is, roughly since the devastation of the European empires by the post-World War Two national liberation movements in Asia, Africa, and Latin America – there is an increasingly widespread belief, pulsating outward from England, that disintegrating homeland of a collapsed global empire, that the world is coming to an end -- through overpopulation, pollution, plague, thermonuclear holocaust, alien invasion, universal madness, computers or insects running amok, the cooling or overheating of the planet, cosmic winds or radiation, a shriveling or exploding sun, and so on. Obviously the one and only form of literary art congenial to such fears is science fiction. Hence the "New Wave" and its leading role in the science fiction of the 1960s and 1970s. We must be clear about one thing: although science fiction does have a cultural influence, it is primarily a cultural expression. Doomsday visions have been around for many centuries, if not millenia, but they become ascendant only during certain historical epochs and for specific historical reasons. J.G. Ballard and the other creators of an apocalyptic science fiction thrive because of certain conditions of the present era. One main goal of this essay is to investigate these conditions. From the outset, we must understand the enormous significance of science fiction in the most developed capitalist nations. Science fiction has attained a modicum of academic respectability in the last decade, but those of us who teach it still find ourselves constantly on the defensive (with our colleagues in the humanities, not, of course, with those in the sciences, much less with our students). A course in science fiction, I have been told, is merely a luxury (though perhaps an attractive one) in the English department, to be sacrificed if the crisis in funds for public education continues. Well, the simple fact is that science fiction is the major non-realistic literary form of the twentieth century, intricately related to all areas of social, historical, and scientific thought. Another object of this essay is to show that a single science fiction writer, in this case J.G. Ballard, reveals to us -- whether deliberately or not remains to be seen -- insights essential to our well-being if not our survival. For Ballard is not some oddity or aberration, but a representative Anglo-American intellectual who has chosen to write science fiction because it is the most suitable vehicle for the expression of ideas he holds in common with many other Anglo-American intellectuals. Ballard makes little pretense that his fantasies of the death of the world or the human species are scientific, plausible, or even possible. The forms of his catastrophes are, in fact, mutually contradictory. There may be too many people, as in "Billenium" (1961), or too few people, as in "The Impossible Man" (1966). The world may get too dry ("Deep End," 1961; The Drought, 1964, 1965) 3 or too wet (The Drowned World, 1962). The environment may suddenly and inexplicably begin to move too fast (The Wind from Nowhere, 1962) or almost as suddenly and just as inexplicably begin to congeal (The Crystal World, 1966). The end may come about through hydrogen bombs, solipsism, suicide, ceaseless urbanization, or in a world-wide "autogeddon" of car crashes. Even within a single work there is often no consistent explanation of why the cataclysm is occurring other than some vague pseudo-scientific theory, presented like a magician's patter and perhaps offered to satisfy the conventional expectations of the readers of science fiction. In The Wind from Nowhere there is one small paragraph of pseudo-scientific mumbo-jumbo about "cosmic radiation" and the “gravitational drag" of "electromagnetic wave forms" to explain an utterly impossible meteorological phenomenon, a wind from the east blowing around the entire planet at a speed constantly increasing five miles per hour per day until it reaches 500 miles per hour and then suddenly begins to die out. The next paragraph offers an alternative suggestion: "Or again, maybe it's the deliberate act of an outraged Providence, determined to sweep man and his pestilence from the surface of this once green earth."4 This actually seems the more plausible explanation, especially since the wind, after steadily increasing for months, begins to die down within minutes of the destruction of a heaven defying pyramid, symbolic of the will and pride of an archetypal capitalist and would-be superman. In The Drowned World, solar flares melt the icecaps. In The Crystal World, "the creation of anti-galaxies" may have caused "the depletion of the time-store available to the materials of our own solar system."5 The Drought contains one passage of explanation for the disappearance of rain, and this utilizes the theme of ecological disaster through pollution. "Millions of tons of highly reactive industrial wastes," "mingled with the wastes of atomic power stations and sewage schemes," have made a "brew" out of which "the sea had constructed a skin... a thin but resilient monomolecular film formed from a complex of saturated longchain polymers.”6 This prevents evaporation; hence all rain ceases; hence the land becomes a burning desert, devoid of rivers, lakes, even well water. The Drought baldly shows that even this early Ballard is not taking his fantasies of disaster seriously on the level of physical event. For not only do all the bodies of fresh water disappear, but the sea itself rapidly and continually recedes. Nowhere does Ballard bother to explain why the sea would diminish, rather than expand, when all fresh water had disappeared into it and no evaporation is taking place from it. Apparently he simply wants to express his vision in the form of a desert world, and the mechanism for creating this desert is, literally, immaterial. (In "Deep End" the oceans have been destroyed by having their oxygen "mined" in order to export an atmosphere for human settlements on other planets; in the loosely connected stories which make up Vermilion Sands (1973) there is no explicit reason why sands have come to substitute for oceans.) Of course in these early novels there is usually at least one passage, and often a constantly reiterated reminder, indicating that the external landscapes are merely projections of an inner landscape. In the later novels, such as The Atrocity Exhibition (1970; published in America in 1972 as Love and Napalm: Export U.S.A.7), Crash (1973), Concrete Island (1973), and High-Rise (1975), even the pretense of science fiction is gradually replaced by an awareness that the bizarre external environment is essentially a projection of a psychological state or a way of perceiving reality. J.G. Ballard, certainly a writer who wants to be taken very seriously (and is so by the British literary establishment), offers to us an endless series of doomsday fantasies as improbable and self-contradictory as oceans that dry up because no water is evaporating from them. At the exact same historical moment, large numbers of scientists and futurologists in England and America are arguing, with the utmost seriousness, that the world really is doomed, quite likely by the millenial year 2000, because there is a population "explosion" or "bomb," because it is too late to stop "ecocide," because computers prove that full-scale thermonuclear war is inevitable, because it is a mathematical certainty that worldwide plague and/or famine will begin in the next few decades, because the earth is about to become catastrophically overheated due to the second law of thermodynamics, because we are on the threshold of a new ice age, because we are about to use up all available sources of energy, because insects are about to become uncontrollable, because the increase of non-white people is causing the human race to become genetically inferior, because it is becoming impossible profitably to extract raw materials from many parts of the world, and so on. Most of the readers of this essay probably accept some of these beliefs, particularly the notion of "overpopulation," so deeply that it will be difficult for me to communicate some of the fundamental ideas of this essay. I know from experience that the question of population is one that is now hard to discuss rationally in England or the United States. In the university, the blandest class becomes enraged at any argument that the world is not now, and is in no foreseeable danger of becoming, overpopulated. Nevertheless, such is the overwhelming consensus of population experts in most of the world, who view the Anglo-American orthodoxy as an archaic neoMalthusian aberration. I shall not attempt to prove these assertions here. All I ask from readers is that they (1) recognize that the population question is extremely controversial; (2) agree that there are many reasonably intelligent, sane, well-informed people around the world, who, like myself, accept the Marxist rather than the Malthusian view of the population question (i.e., that the world's ability to support the standard of living for each human being is rapidly increasing, rather than decreasing, and will continue to do so into the foreseeable future); (3) allow that apparently self-consistent and plausible arguments can be advanced on both sides of the population question; (4) open their minds to the possibility that one's views on population, as on many other questions, may possibly be determined by something other than the objective truth or falsity of a belief, and that this "something" may include official propaganda, a body of assumptions common to a culture, the outlook of a social class dominating the means of communication, or the point of view of one's own social class. I use the question of population because it is the key to all other questions of global catastrophe. To all readers who are prepared to go this far I say: Let us now consider the possibility that J.G. Ballard's implausible pseudo-scientific fantasies and the "scientific" apocalypses of Paul Ehrlich and the Club of Rome spring from the same sources. This has nothing to do with possible influences from science fiction to science or vice versa. Certainly Ballard is not just some kind of literary mouthpiece for certain scientific theories, as the self-contradictory nature of his fantasies proves. And certainly I am not arguing that The Population Bomb was published in 1968 because Paul Ehrlich had been reading too much Ballard and other Anglo-American science fiction of global disaster. My underlying theory is that Anglo-American science fiction and predictive Anglo-American scientific thought are both conditioned and determined by the socio-economic ambience of a collapsed British empire and a disintegrating American empire."8 I shall try to test this theory in the particular case of the most eloquent and imaginative of the prophets of doom, J.G. Ballard. To avoid another misunderstanding, which usually takes place when a Marxist addresses an audience profoundly miseducated about Marxist criticism, when I use the word "determined" I do so in the Marxist, not the positivist, sense. That is, social reality and one's class situation determine all forms of consciousness, including artistic and scientific, in the sense of constituting the range and limitations of what one finds conceivable and congenial. This determination (i.e., what shapes and forms something) is not in any sense part of a philosophic determinism. Though we all have ideas and feelings, fears and desires, plans and fantasies shaped and formed by our physical and social environments, each of us, including J.G. Ballard, I the writer, and you the reader, is free, within historical limitations, to choose among many conflicting patterns of thinking. Ballard might persuade me that the apocalypse is at hand and that it will take the form of a psychological autogeddon. I might persuade you that such a vision is a fantasy alien to the experience of the vast majority of human beings on the planet. But none of us is capable of viewing the world from the perspective of a pre-Columbian Aztec priest, the wife of a seventeenth-century New England Puritan minister, or any human being living in the year 2100, to use extreme examples. Let me try to penetrate at once to the heart of Ballard's imaginative creation. His novels seem to me to fall rather neatly into two groupings: the early novels of world-wide physical catastrophe (The Wind from Nowhere, The Drowned World, The Drought, The Crystal World) and the later novels of psychological destruction (The Atrocity Exhibition, Crash, Concrete Island, High-Rise). Of course there is plenty of psychological havoc in the early novels and physical mayhem in the later. Unifying all these novels, however, is the theme of the global catastrophe as an external projection of a deranged inner landscape. Prior to any of these novels, Ballard was publishing short stories, and in one of the earliest, "The Overloaded Man" (1960), he prefigures the most recent forms of his imaginings and provides us with a précis for the underlying content of them all. In this story he shows quite explicitly that the source, or at least one crucial source, of the central problem of all his fiction is the historical dichotomy between subject and object, a dichotomy which he perceives as becoming catastrophic as bourgeois society itself disintegrates. In "The Overloaded Man" it is explicitly the lone petty bourgeois intellectual who destroys the entire world not by bombing it with nuclear weapons or too many people but by withdrawing himself from it. The protagonist's solipsism is equated with suicide, murder, and global catastrophe. In short, "The Overloaded Man" is a paradigm for Ballard's artistic opus. The story is set in the near future, subtly indicated by the slight increase in automatic domestic appliances, a slight exaggeration of late 1950s suburban plastic architectural trends, a somewhat more leisured existence for the technocratic social class, and a small deterioration of social relationships within that class. The first sentence summarizes the story of the title character: "Faulkner was slowly going insane."9 Two months have passed since he resigned from his job as "a lecturer at the Business School," and he has been lying around the house, pretending to his wife that he is "still on creative reflection." As soon as his wife, dressed in "the standard executive ... brisk black suit and white blouse," leaves for her job, Faulkner is free "to begin his serious work" (pp.72, 73). This consists of turning all of objective reality into meaningless abstractions, "systematically obliterating all traces of meaning from the world around him, reducing everything to its formal visual values" (p.78). He finds it "pleasant to see the world afresh again, to wallow in an endless panorama of brilliantly coloured images. What did it matter if there was form but no content?" (p.76) His method is the same as that used by the main character in The Atrocity Exhibition (Love and Napalm); Faulkner is able to convert houses, trees, people, whatever, into "geometric units," pieces of a gigantic "cubist landscape." In this early story, Ballard takes us step by step, in simple narrative, through the whole process. Faulkner has his first success with consumer goods, for reasons explicitly related to the essence of capitalism, which converts all good things into "goods"; that is, commodities: "Stripped of their accretions of sales slogans and status imperatives, their real claim to reality was so tenuous that it needed little mental effort to obliterate them altogether" (p.75). After he has then "obliterated the Village and the garden," he begins "to demolish the house." He sinks "deeper and deeper into his private reverie, into the demolished world of form and colour which hung motionlessly around him." Soon he has "obliterated not only the world around him, but his own body, and his limbs and trunk seemed an extension of his mind, disembodied forms whose physical dimensions pressed upon it like a dream's awareness of its own identity" (p.82) In other words, he has achieved solipsism, reducing all objective reality to an appearance of his own mind. Solipsism is a danger inherent in bourgeois ideology right from the start, in its Cartesian assertion that I exist because I think. Faulkner's neighbor, also a lecturer at the Business School, had warned him of this danger: “The subject-object relationship is not as polar as Descartes' Cogito ergo sum suggests. By any degree to which you devalue the external world so you devalue yourself.” But Faulkner plunges down his chosen path to annihilation, converting his wife into "a softly squeaking lump of spongy rubber" as he murders her, and drowning himself in order to become, in the very last word of the story, "free." The tendency toward solipsism in bourgeois ideology is held in check as long as the bourgeoisie is rising or ruling as a social class, extending or maintaining its "freedom." During these periods, the bourgeois split between subject and object manifests itself in what Ballard aptly calls Crusoeism: the individual man of action, relying on his own wits and ingenuity, and sometimes aided by inferior beings, conquers the natural and social environment. Ballard displays collapsing bourgeois society turning the Crusoeism of the rising bourgeoisie inside out. The hero of "Deep End" is "a Robinson Crusoe in reverse,"10 trying to restore the last technological remnants on an abandoned earth. The hero of The Drowned World shows "inverted Crusoeism" in "the deliberate marooning of himself."11 The protagonist of Concrete Island, an elaborate parody of Robinson Crusoe, expends his life attempting to "dominate" and to "escape from" an island of weeds and old cars which he could leave any time he chooses to walk away. Ballard is now showing us the bourgeois ideal of the "free" individual as a prisoner in the smallest of cells, his own ego. In his early works, Ballard sometimes offers a wishful alternative to alienation and solipsism. It is a vision of cosmic unity with intelligent beings throughout the macro-history of the universe. This vision, reminiscent of Olaf Stapledon and carried forward in different ways, in the works of Arthur C. Clarke and Ursula Le Guin, is expressed as a revelation in "The Waiting Grounds" (1959): "Meanwhile we wait here, at the threshold of time and space, celebrating the identity and kinship of the particles within our bodies with those of the sun and the stars, of our brief private times with the vast periods of the galaxies, with the total unifying time of the cosmos…”12 Before long, this unity between the microcosm and the macrocosm will be lost for Ballard and it will become the object of an endless quest, always reducing itself to the jungles and deserts of the entrapped and tormented individual psyche. In "Build-Up" (1960), another of these revealing early stories, Ballard projects an endless three-dimensional city whose economy is based on the final commodity: space, which sells for about one dollar a cubic foot. The protagonist, trying to located what he calls "free space" ("in both senses") discovers that time itself has become nullified by this ultimate form of capitalist super-development. His odyssey toward some limit of the boundless city leaves him right back where he started, defined with utmost precision in the final words of the story: "$SHELL x 10n." Brian Aldiss has called The Wind from Nowhere, the first of Ballard's novels, a pot-boiler.13 It is true that the narrative method is straightforward, several adventure stories are interwoven into the apocalypse, and there is a not unhappy ending in which a few of the less unsympathetic characters survive. But in this novel Ballard for the first time develops at full length many of his characteristic themes, and certainly this is a book with a serious message. Although London is explicitly called "a city of hell" (p.54) only the wind has begun its havoc, nature's desolation is clearly revealing rather than creating a dry, sterile human wasteland. The main point-of-view character, Donald Maitland, is at the very opening in the act of deserting his wife, the spoiled, hedonistic only child of a wealthy shipping magnate. Like the principal character in many of Ballard's tales, Maitland is in a branch of medicine or biology. His field is "research into virus genetics -- the basic mechanisms of life itself," which, unlike "research on petroleum distillates or a new insecticide," merits little financial support in this profit-oriented society (p.9). So he is bought and kept by a rich wife. The world they both inhabit is barren and exploitative, and its rulers already maintain vast armed forces to preserve their own wealth, power, and comfort. Both "people in the War Office" and "the politicians" are merely carrying out their normal jobs in abnormal conditions when they decide to provide shelter only for the privileged: "As long as one-tenth of one percent of the population are catered for, everybody's happy," Maitland's friend in the Air Ministry tells him, "But God help the other 99.9" (p.21). Meanwhile in America the likely Democratic presidential nominee is General Van Damm, NATO Supreme Commander, whose death in a car crash in Spain while on a secret visit to Generalissimo Franco is being "hushed up for political reasons" (p.34). The dry and dusty inferno created by the wind, punctuated by "the sounds of falling masonry," is a symbolic representation of the state of capitalist society. The main symbolic figure in The Wind from Nowhere is the multimillionaire Hardoon, who owns "vast construction interests" and is also, like Maitland's father-in-law, a shipping magnate. (One suggestion for his identity is the name of the one merchant ship mentioned -- the Onassis Flyer.) Hardoon is an early avatar of a figure who will appear in various forms throughout the rest of Ballard's novels: the man of action and power who seeks to master nature, to subject the natural and human worlds to his own will and pride. This figure is the hero of much pro-capitalist science fiction of the 1930s in Germany, England, America, and among Russian émigrés such as Ayn Rand. Hardoon is a caricature of this early science fiction hero. In the midst of the natural cataclysm, Hardoon constructs the only building supposedly capable of withstanding the storm, a gigantic pyramid which reminds someone of Cheops. He recruits a private fascist army, complete with black uniforms, black leather boots, and the emblematic white seal of his pyramid, obviously an ensign of death. When Maitland meets Hardoon, the man of power sneers at the intellectual as part of "the weak" incapable of understanding "the strong." Then he explains himself, in a passage which could come right out of Ayn Rand or any number of the positivists and technocrats dominant in science fiction until the mid-1950s:

Needless to say, the destructive forces of nature win, and "the millionaire" is left "staring upward into the sky like some Wagnerian super-hero in a besieged Valhalla" (p. 156). So ends the lone bourgeois hero. The nemesis of this superman does not appear in this novel, though he is prefigured somewhat by Maitland. This is a quietistic introvert, a biologist or doctor, who subordinates his own identity in nature. He is the principal figure of the subsequent three novels. The Drowned World presents the characteristic structural conception of Ballard's fiction. Just as the drowned planet projects an inner landscape, so the body and psyche of the protagonist recapitulate in microcosm the world of nature. The sun, almost as a conscious power, is burning off the ionosphere and reclaiming the planet for itself. The Earth is becoming a steaming sea mingled with swamp and jungle, the artifacts of civilization are being inundated by water and taken over by reptiles, and the most sensitive human beings find their own minds booming to rhythms of the sun as they drift back into a primeval and preconscious world. Ballard presents as the highest reality produced by our own century paintings by Delvaux and Ernst, which prefigure scenes to be enacted out quite literally as the minds of the human race sink into the seas of the unconscious:

Later these nightmare paintings, the external jungle, and the shared nightmares of the main characters merge into each other: the painting by Ernst and the jungle "more and more... were coming to resemble each other, and in turn the third nightscape each of them carried within his mind. They never discussed the dreams, the common zone of twilight where they moved at night like the phantoms in the Delvaux painting" (pp.73-74). The embodiment of death, as painted by Delvaux, appears in the person of Strangman, a man as white as bones, dressed in white, and considered a dead man by his crew of Black pirates. Strangman is, like Hardoon, an avatar of the man of power, pride, will, and egoism who seeks to conquer nature. He appears, with machinery and a flotilla of half-trained alligators, to reverse the course of nature's reclamation. When he succeeds in pumping out the city of London, "the once translucent threshold of the womb had vanished, its place taken by the gateway to a sewer," and London again resembles "some imaginary city of hell" (p.121). Strangman's nemesis is Dr. Robert Kerans, the protagonist, a biologist, isolated, quietistic, impotent, "too passive and introverted, too self-centered" (p.74) to take command of the situation. Kerans seeks to swim back into his own "drowned world of my uterine childhood" (p.26), to recapture "the amnionic paradise" (p.64), to merge with both sea and sun, to become the new Adam. He does succeed in destroying Strangman's work, in flooding London once again, but then he leaves his symbolic Beatrice behind to lose himself in an endless self-destructive lone odyssey "through the increasing rain and heat, attacked by alligators and giant bats, a second Adam, searching for the forgotten paradises of the reborn sun" (p.158). The Drowned World formulates the trap in which Ballard has been thrashing around ever since. To comprehend the larger relevance of this predicament, let us look at some difficulties posed by his symbols and characters. First we must recognize that Kerans' quest is, at bottom, destructive of all human relationships and ultimately suicidal. In seeking to merge with the sun and the sea, he renounces his humanity, in all senses. His quest for the sources of life is, in the last analysis, a search for death. On the other hand, Strangman, the symbol of death-in-life, is actually working, whatever his piratical intentions, to reclaim part of the planet for humanity from the alien forces of nature. So Kerans and Strangman are yoked, as opposites in a larger unity of life and death, which I think Ballard wishes us to perceive as a yin-yang. On the literal level, this involves a psychological doubling. Kerans descends in a diving suit into the drowned London planetarium, sees himself in a mirror, and "involuntarily" shouts "Strangman!" at his own reflection. Strangman understands Kerans' quest so deeply that he turns it into a sardonic joke:

Or, looking at Kerans in the diving suit, Strangman responds, parodying the author as well as his projected character:

When he does dive, Kerans subconsciously tries to lose his identity in the water and the drowned image of the heavens in the planetarium by killing himself. He blames his brush with death on Strangman, but it is actually Strangman's men who save him from himself, only to attempt to kill him ritually later on, as they crucify him as an embodiment of Neptune. The fundamental paradox here is that Ballard's quietistic, suicidal, nature-loving hero is actually another avatar of his "Wagnerian super-hero." In fact his mission is even more cosmic, his hubris more presumptive, than that of a Hardoon or Strangman. One might compare this relationship at length to that between Ishmael, the would-be suicide who seeks to lose himself in the ocean, and Ahab, who defies and seeks to master nature. But there is a profound difference between Melville's art and Ballard's that has to do with basic values. Despite all the carnage and death in Moby Dick, that book affirms life and the ties of loyalty and trust which bind human beings together and which it is madness to sever. Despite all the yearning for life in Ballard's fiction, it is ultimately a literature of despair, negation, and death. Kerans' impulses, however cloaked in fantasies of embodying the sun and the sea, are merely another form of the madness incarnated by Faulkner in "The Overloaded Man." Kerans, and through him his author, is expressing a dying society. Ballard of course knows this. What he means by the "surreal" or “super-real" is the psychological condition which he himself partly incarnates. The symbols of our age are for him its most horrifying historical events, and the progress of his fiction is largely into a deepening exploration of the psychological content of these events. The nuclear bombs of Love and Napalm were already the annihilating symbols of "The Terminal Beach" (1964); the auto crashes of Crash and Concrete Island were just as universally final in "The Impossible Man." In The Drowned World he explicitly states his unifying conception of historical and psychological events:

My criticism is that Ballard does not generally go down far enough below the unconscious to the sources of the alienation, self-destruction, and mass slaughter of our age. He therefore remains incapable of understanding the alternative to these death forces, the global movement toward human liberation which constitutes the main distinguishing characteristic of our epoch. The real nemesis of militarism, exploitation, and the rape of the environment is not the insane overloaded man who is seeking to be "free" by oblitering the entire world, nor the suicidal quietist, such as Dr. Robert Kerans in The Drowned World, Dr. Charles Ransom in The Drought, or Dr. Edward Sanders in The Crystal World. Nor is it the main figure of Love and Napalm, a doctor trying to cure the world by rearranging its pieces; nor Robert Maitland, the architect in Concrete Island, who maroons himself amidst British freeways; nor James Ballard, the revealingly-named narrator and protagonist of Crash (the only novel narrated in the first person), whose greatest pleasures are (1) looking in the rear-view mirror to see the man of power, Vaughan the "hoodlum scientist," copulating with Ballard's wife and then beating her; (2) having anal intercourse with Vaughan; and (3) finally arranging to follow Vaughan's leadership by killing himself, together with at least one attractive woman, in a car crash. Beyond the scope of Ballard's death-worshipping imagination are the people rescuing the world from the state of being that determined that imagination. Of all Ballard's works, the one in which he comes closest to perceiving the rising forces of our epoch is a short story, "The Killing Ground," written in 1966 during the American invasion of Vietnam and clearly intended in part as propaganda against it. But even in this story he ends by turning away from his own best insights. The time is "thirty years after the original conflict in south-east Asia," and "the globe was now a huge insurrectionary torch, a world Viet Nam.”14 The scene is the Kennedy Memorial at Runnymede on the banks of the Thames, and the point-of-view is that of Major Pearson, leader of a scraggly band of "rebel" guerrillas harassing the technologically superior American invasion forces. In one striking passage, Ballard briefly imagines the masses of people creating a better future out of this holocaust: "...the war had turned the entire population of Europe into an armed peasantry, the first intelligent agrarian community since the 18th Century. That peasantry had produced the Industrial Revolution. This one, literally burrowing like some advanced species of termite into the sub-soil of the 20th century, might in time produce something greater" (p. 144). But that seems a shadowy hope, and certainly Ballard is unable to imagine not only that future but the present society of his insurrectionary peasantry. They, like the impotent Major Pearson and his ragged soldiers, are dominated by the "immense technology" of the American invaders, who seem like "some archangelic legion on the day of Armageddon" (p.140). The Americans had won in Vietnam, had then "occupied the world," and at the end of the story they have killed Major Pearson and destroyed his unit. We must remind ourselves who did win in Vietnam. American technology was not invincible; the Tet offensive took place a little over a year after this story was published; within five years the vaunted American military machine was a shambles; and in less than a decade a socialist society. We can grasp the ironies of Ballard's misunderstanding of history if we take a close look at two interrelated works prior to "The Killing Ground" -- "The Garden of Time" (1962) and The Crystal World. "The Garden of Time" is almost pure allegory, a rarity for Ballard. It shows the last stand of feudalism, incarnated by Count Axel, a figure apparently derived both from Axel, the symbolist closet drama by Villiers de I'Isle Adam and from Edmund Wilson's interpretation of the play in Axel's Castle. In "The Garden of Time" Axel's castle, garden, and exquisite life with his flawless wife are besieged by "an immense rabble" appearing on the horizon and ineluctably advancing upon him across the plains and hills. Variously described as "the mob," a "horde," and "a vast concourse of laboring humanity," this army of "limitless extent" obviously represents the revolutionary masses storming the final symbolic bastion of feudal privilege, grace, and beauty. Axel's only defense is the crystal flowers of time in his garden. While growing, each crystal flower seems "to drain the air of its light and motion." When picked, each flower begins "to sparkle and deliquesce," causing an abrupt "reversal of time." As this happens, the entire revolutionary concourse is "flung back" away from the castle. Time, in the form of the crystal flowers, of course runs out for the Count, and he and his wife are left to stand as stone statues surrounded by the vulgar mob that overwhelms his ruined estate. Those who have read The Crystal World will immediately recognize the cosmological symbolism of the crystallized plants, which represent a congealing of time and an alternative to the world of human activity. But the historical symbolism may seem irrelevant to the novel. I don't think so. In The Crystal World, the force inevitably advancing is not the mass of oppressed people but some mysterious process that transmutes all organic matter into crystals. These crystals, like those in "The Garden of Time," drain light and motion, congeal time, and "deliquesce" in sparkling beauty when removed from their sustaining jungle environment. They are on their way to taking over and transforming the planet; no force will be able to stop them. The protagonist, Dr. Edward Sanders, leaves his position as head of a leprosarium, representing an apparently selfless dedication to help follow human beings, to become eventually a devotee of the crystal world and what it represents. As he writes during the process of his conversion:

All this may seem exactly the opposite of the historical movement of "The Garden of Time." But then we need to take a close look at the historical and geographical setting for The Crystal World. The story is set very neatly on the equator and at the vernal equinox. This place and time obviously have large symbolic significance in Ballard's cosmological yearnings. But more specifically the place is Africa, and the time is during the rising tide of the wars of national liberation sweeping across the continent. At the end of World War II the vast lands of Africa were still almost entirely owned by a handful of tiny European countries -- England, France, Belgium, Spain, and Portugal. England and France together possessed over two-thirds of the continent. By the time The Crystal World was published in 1966, most of the countries of Africa had attained their independence, and liberation struggles were spreading rapidly in the others. The empire of Ballard's own nation was crumbling almost week by week. In the nine years preceding the book, thirteen of Britain's African possessions (Gold Coast, British Togoland, British Somaliland, British Southern Cameroons, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Uganda, Tanganyika, Zanzibar, Kenya, Nyassaland, Northern Rhodesia, Gambia) broke loose from the empire. Although Britain purported to be "giving" these lands their freedom voluntarily, clearly it was bowing to the rising rebellions of the African peoples themselves, spearheaded by the armed struggle of the Mau Mau in Kenya and inspired by the Pan-African socialist ideology of leaders such as Kwame Nkrumah and Julius Nyerere. By 1966 several of these newly independent nations, including Nigeria, Ghana, and Tanzania, were helping to provide world-wide leadership for the emerging non-aligned African-Asian-Latin American bloc in their accelerating attacks against British, European, and U.S. imperialism. These facts are hardly irrelevant to Ballard's story or its symbolic content, since he himself introduces into The Crystal World the subjects of imperialism in Africa, including the role of European mining companies and the rebellions against the European empires. The Crystal World is set explicitly in the Cameroon Republic, though Ballard has changed the country to suit his symbolism. Dr. Sanders is arriving in the fictional Port Matarre on a steamer from Libreville (capital of Gabon), but it is Gabon, not the Cameroons, that sits astride the equator (and, interestingly enough, the Crystal Mountains are also in Gabon, just upriver from Libreville). Ballard's fictional Cameroon Republic is still under French military control, though in actuality the country had become politically independent in 1960. (The date of the action is established as later than 1960 by an orbiting Echo satellite and retrospective narration about the Katanga revolt of 1960-1962.) The main industry is diamond mining, under the control of European corporations, though the Cameroon Republic has, in fact, virtually no mining for jewels. Certainly the diamond mining has something to do with Ballard's main theme and main symbols. There are "the French owned mining settlements, with their over zealous security men" (p.17) and their "warehouses bearing the names of the mining companies" (p.55). "...the diamond companies don't intend to let anything get in their way" (p.81). When the rain forests begin to crystallize, huge jewels are smuggled out, causing the mining companies' "share prices on the Paris Bourse" to soar "to fantastic heights" (p.58). When a man is sent to investigate, the "vested interests" see to it that he ends up in the river (p.59). The "natives" smuggle out fantastically jewelled leaves and branches and sell them as commodities in the town marketplace. Two explicit themes are the self-destroying search for El Dorado and the myth of Midas. In the face of man's frantic efforts to rip up the earth in the search for wealth in the form of crystals, nature seems to respond by crystallizing all of itself, including man. It is “time with the Midas touch" now (p.75). And people at first respond by converting the products of this fabulous process into commodities and cash as they do ordinarily with gems. Ballard relates this set of symbols directly to the African liberation movements -- in opposition to them. The crystal plants in The Crystal World have a function very close to those in "The Garden of Time." Dr. Sanders' new-found lover, a Frenchwoman, darkly tells him "of some kind of humiliation" she had experienced in the Congo "during the revolt against the central government after independence, when she and several other journalists had been caught in the rebel province of Katanga by mutinous gendarmerie" (p.36). The Katanga revolt was of course financed by the European mining companies and the C.I.A.; that same “mutinous gendarmerie" were to become an anti-imperialist force, fighting in Angola, first against Portugal and then against the C.I.A.-supported invaders from Zaire and South Africa, returning later to Zaire as revolutionary socialists. In Ballard's imagination these revolutionaries exist only as some dark, sinister force committing unmentionable acts on lone white women. The anti-imperialist forces in Ballard's semi-imaginary Cameroons may actually, and at least symbolically, have triggered the crystallization process that freezes time and history. That process had begun upriver, at the emerald and diamond mines around the symbolically named settlement of Mont Royal. Shortly before, the rebel forces had occupied precisely these locations. When Sanders arrives, he finds "this isolated corner of the Cameroon Republic was still recovering from an abortive coup ten years earlier, when a handful of rebels had seized the emerald and diamond mines at Mont Royal, fifty miles up the Matarre River" (p.10). So this "inner landscape" is a projection of historical, as well as psychological, events. This is "a landscape without time" (p. 14), the fond hope of Count Axel and all others seeking to freeze history. At first when Count Axel plucks his crystal flowers from his garden of time, he is able to make the "concourse of laboring humanity," that advancing vulgar "mob" and "rabble," actually disappear. As Dr. Sanders, the agent of Ballard's own odyssey, succeeds in losing himself in the crystal forest of a mythical Africa, Ballard is able to make the liberation movements of the 20th century, fitly represented by the African anti-colonial forces, actually disappear at least in his fiction. Sanders wants to stop time, so he plunges into the time-congealed crystal world. As Ballard shows us in "The Garden of Time" the inner meaning of the desire to stop time is to stop history. He also shows us in that story that the inner meaning of the desire to stop history is to stop revolution in order to preserve archaic privilege and order. All this so far is on a rather general, highly symbolic level. But Ballard also directly presents to us his own images of the people in revolt in our century, the people dismembering his empire and leaving many British intellectuals, including himself, with the deepest convictions that the apocalypse has come and the whole world is dying. And these images are so disgustingly racist that they might embellish a Ku Klux Klan rally. Just as Count Axel is horrified by the thought of the unleashing of the laboring masses, J.G. Ballard seems terrified by the image of the unleashing of the non-white masses. In the chapter "Mulatto on the catwalks," immediately after we are told of the unspeakable outrages of the Katangan gendarmerie, Dr. Sanders is for the first time attacked by a murderous mulatto, who moves "with the speed of a snake" (p.41). This "giant mulatto" (p.83) reappears with another assassin, a knife-wielding "Negro" with a "bony pointed face," to ambush Sanders in a maze of images reflected in the mirrors of an elegant European mansion out in the crystallized rain forest. Still later, in the chapter entitled "Duel with a crocodile," a crystallizing crocodile sidles clumsily toward Sanders. "Feeling a remote sympathy for this monster in its armour of light, unable to understand its own transfiguration," Sanders almost fails to note the gun barrel between the jewelled teeth. The bejewelled crocodile is merely the latest disguise for the treacherous mulatto hidden inside. Sanders kills him, and pauses briefly over the body with its glistening "black skin" (p.143). The only apparently civilized Black person in The Crystal World turns out to be one of the treacherous accomplices in this attack on Sanders, and he too must be disposed of by a shot from a white man. In The Drowned World, the would-be assassins of Dr. Robert Kerans are the horde of "savage" Blacks ruled by Strangman. They speak in a Negro minstrel dialect and are constantly motivated by a primitive superstitious "fear and hatred of the sea" (p.124); and they therefore try to torture Kerans to death to the tune of "The Ballad of Mistah Bones" hammered out on bongos and a skull with a "rattle of femur and tibia, radius and ulna" (p. 125). Chief among them is "Big Caesar," exact counterpart of the "giant mulatto" of The Crystal World, though instead of appearing like a snake and a crocodile, Caesar is "like an immense ape" (p. 128) with a "huge knobbed face like an inflamed hippo's" (p.124). In the four novels Ballard published in the 1960s, it is ostensibly some component of nature that goes berserk, though this is always at least an expression, if not an outright product, of human affairs. In the four novels published so far in the 1970s the apocalypse is man-made. In the first four novels, it is nature that obliterates twentieth-century urban civilization, with its machines and technology. In the last four novels, all located in one superurban environment (London), nature has disappeared and it is twentieth-century civilization that is self-destructing through its machines and technology and resulting psychological aberrations. In Concrete Island, for example, all that remains of the natural world is a small triangular plot of deep grass and weeds formed by the intersection of freeways, and in High Rise the fictional world is a self-contained apartment complex, something like a chunk of the unending urban hell of "Build-Up." The unifying quest of the recent novels is no longer for a merging with nature, in the form of the ocean, sun, or forest, but with the machine itself. This quest characteristically takes the form of a bizarre attempt to achieve "a new sexuality born from a perverse technology.”15 Love and Napalm: Export U.S.A. sets forth this "new sexuality"16 as the equation of human sex and "love" with car crashes, assassinations, napalm, B-52 raids, thermonuclear weapons, disembodied fragments of the human body, and the lines and angles of freeways, machines, wounds, and buildings (the sexiest structure is a multi-level parking garage that suggests both rape and death). The central symbol of this quest is the automobile. Back in the short story "The Subliminal Man" (1963), Ballard had projected the automobile and the concrete milieu we construct for it as the basic economic and psychological fact of decaying capitalist society:

In "The Subliminal Man" Ballard did something extraordinary for him and unusual for any Anglo-American writer of science fiction: he subjected this future automobilized monopoly capitalist society to a rigorous analysis, showing how the psychology of the people within it is determined by the political economy. The vast forces of production, still ruled by capitalist social relations, become a colossal alien power, constantly producing more and more commodities and increasingly incapable of satisfying real human needs. If the commodities turned out by capitalist production actually satisfied human needs, they could be sold through rational description. Since this is clearly not the case, in capitalist society today advertising attempts to evade or manipulate our rational thought processes and to stimulate irrational desires. An entire industry spends millions of dollars annually just on research to discover new advertising techniques designed to exploit and intensify our desires for competitive success, power, riches, admiration, and sensation. In some cases less money is spent on products than their containers, which are intended to turn the aptly named "consumer" into a mindless robot, as Gerald Stahl, Executive Vice-President of the Package Designers Council, cogently explained: "You have to have a carton that attracts and hypnotizes this woman, like waving a flashlight in front of her eyes." In "The Subliminal Man" Ballard merely extrapolates from one advertising technique already utilized to reach the subconscious directly, subliminal messages beamed directly into the retina too fast to be recognized consciously. In a few pages, Ballard creates a nightmare vision of a monopoly capitalist society using this technique on a grand scale, successfully reducing each person to an automaton of mindless consumption, endlessly working, purchasing, and driving back and forth to jobs and supermarkets in a shiny new automobile on vast expressways under gigantic subliminal advertising signs whose shadows swing back and forth "like the dark blades of enormous scythes."18 The alienation of people within such a society and their increasing obsession with catastrophic death is a subject for deep exploration, and this is the primary subject of Ballard's subsequent fiction. The greatest strength of this late fiction is that it penetrates profoundly into the morbid psychology that comes from living in such a society; its most critical weakness is that in pursuing this exploration, Ballard loses sight of the underlying causation of the psychopathology of everyday life in decaying capitalism. He leaves behind his own best insights, in stories such as "The Overloaded Man," "The Impossible Man,” “Build Up," and "The Subliminal Man," which show the individual human being as the victim of an inhuman social structure, and begins to stand the world on its head, making the psychology of the individual the cause rather than the product of the death-oriented political economy. Underlying the elaborate verbal structure of the late fiction are some fairly simple, in fact simple-minded, ideas about social reality. Indeed, the formal pyrotechnics disguise as much as they reveal of the ideational content. Clad in an elegant costume is the tired old idea that human nature is basically brutish and stupid, that people are inherently perverse, cruel, and self destructive, and that's why the modern world is going to hell. High-Rise, his latest novel, is virtually a parody of this notion. Such a vision, I believe, is merely a projection of Ballard's own class point of view, a myopia as misleading as the national and racial point of view in the earlier novels and intimately related to that narrow outlook. Now some may think it unfair or inappropriate to discuss Ballard's late fiction as essentially political statement, but Ballard's recent art is profoundly political; in fact its content is most intensely political when its form is most "surreal." For example, Love and Napalm: Export U.S.A., the most plotless, fragmented, surrealistic, and anti-novelistic of his long fictions, includes the following as explicit primary subjects: the Vietnam War; Hiroshima and Nagasaki; the massacres in Biafra and the Congo; the presidential candidacy of Ronald Reagan; the assassinations of Malcolm X, John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King, and Robert Kennedy; Ralph Nader's campaign for automobile safety; the use of napalm as a weapon; and the use of sex as a commodity. An author who did not want his work to be discussed politically would (or should) choose different subject matter. In Love and Napalm Ballard presents the fashionable liberal idea that "America is a land of violence"; that's the fundamental lesson, he tells us, of Hiroshima and Dallas, Los Angeles and Memphis, Hollywood and Saigon. (See, for example, the section entitled "The Generations of America," a four-page list of who shot instead of begot-whom in America.) This is summed up commonly in that cliché we've been hearing since 1963: "Oswald may have pulled the trigger, but wasn't it all that hate and violence in America that loaded the gun?" With all its fancy tricks, this is one of the dominant messages of Love and Napalm, which actually ends with these final words: "Without doubt Oswald badly misfired. But one question still remains unanswered: who loaded the starting gun?" The implied answer is that we did, with our morbid psychology, which will lead to the first word of the book, "Apocalypse." But is it true that Lee Harvey Oswald, as well as the assassins of Malcolm X, Robert Kennedy, and Martin Luther King, were just products of the diseased psychology of the American people? Those of us who believe there is overwhelming evidence indicating the direct involvement of the secret government of the U.S.A. in the assassination of each of these men make quite a contradictory political analysis from that offered by Love and Napalm. For if indeed the government must carry out assassinations of popular leaders and then engage in elaborate cover-ups based on stealth and deceit, this would certainly suggest that it does not express the will or desires of the American people. The same kind of contradiction appears for each of the other political premises of Love and Napalm. The book argues, for example, that the Vietnam War went on so long because it appealed deeply to the subconscious sexual desires of the American people. In a parody of consumer research, and in a kind of self parody, Ballard writes:

But the fact is that the American people's massive and militant opposition to the war was one of the principal reasons the government could not continue to conduct it. This anti-war movement, one virtually unprecedented in history, appears in only one passage in the book:

Sure this is cast as parody, but that is essentially mere disguise, for any recognition of the historical and moral significance of the anti-war movement would cause the nightmare vision of the book to dissolve just like any other bad dream. This brings us back to the automobile, the central symbol of Ballard's nightmare. Ballard's choice of the automobile as emblem and synecdoche for the apocalypse is splendid. In the U.S., "25 cents out of every dollar spent at retail is connected with the auto... The automobile annually consumes... 64.2 percent of the Nation's rubber production, 21 percent of all its steel, 54.7 percent of the lead, 40 percent of the malleable iron, 36.5 percent of the zinc.”19 As Dutch economist Andre van Dam notes: "Each year automobiles kill 180,000 people worldwide, permanently maim 480,000, and injure 8,000,000. Car accidents account for 3% of the gross national product in the industrial nations, a huge sum that should be subtracted from the GNP rather than added to it."20 And in the words of "American Ground Transport," a report submitted to the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly: "We are witnessing today the collapse of a society based on the automobile."21 But Ballard's failure to understand the source of this collapse, or rather his failure to carry forward the understanding he reached in "The Subliminal Man," leaves him mistaking the end of capitalism for the end of the world. First, the Los Angelesation of capitalist society has not been primarily a product of Anglo-American mass psychology. As the report cited above thoroughly documents, it was the giant automobile companies that consciously, systematically, and ruthlessly destroyed all competing forms of mass transportation. Prior to the Depression, most large American cities had a virtually pollution-free electric railway system. Between 1935 and 1956, General Motors alone bought up "more than 100 electric surface rail systems in 45 cities," disposed of them as scrap, set up subsidiary bus companies with fleets of General Motors buses, and used its enormous political leverage to have the cities redesigned for automobiles and buses.22 Los Angeles is indeed the model city for what the automobile monopoly could do:

And if the slogan of General Motors was once "What's good for General Motors is good for America," it's true that GM must long since have added parenthetically "Today America, tomorrow the world." But frightening as the spectacle may be of the world being converted into a gigantic Los Angeles, no such possibility exists in reality. Ronald Reagan's cheerful boast that "We could pave Vietnam over and be home by Christmas," with its ironies too complex to count, proved to be just as phantasmagorical as Ballard's cheerless vision of the same kind of event. The empire based on the auto economy is no longer expanding, but collapsing and dying, largely because the majority of people in the world are in the process of creating a more advanced social system. Although Ballard's brilliant imagination penetrates deeply into the symbolic significance of the automobile, it is determined by his class outlook and therefore operates within very narrow limits. From his class point of view, automobiles exist only as objects of consumption -- first economic and now primarily psychological and destruction. In Crash they have come to consume and embody an anti-human sexuality. In Concrete Island they are not only the vehicle of self-destruction but of willful self-isolation in the cellular island prison formed by a society of speeding machines, concrete speedways, and "normal" individuals who race back and forth to work and empty relationships with other individuals. The millions upon millions of automobiles just appear ready-made on the scene. With the notable and revealing exception of "The Subliminal Man," in which Dr. Franklin has to augment his income by working Sundays as "visiting factory doctor to one of the automobile plants that had started Sunday shifts" (p.255), there is no sense whatever that automobiles and their milieu are physically constructed by the tens of millions of people around the world extracting raw materials from the earth, manufacturing steel, tires, glass, concrete, and petroleum products, and assembling the finished machines in factories designed to turn them also into facsimiles of automata. Ballard, because his outlook is that of a minority sub-class of petty bourgeois intellectuals rather than that of the vast majority of people who work in the mines, mills, factories, fields, refineries, offices, hospitals, transportation systems, stores, and forests of the world, sees the automobile only as something that is consumed or consumes. Hence the exquisite symbolic logic of the cannibalistic and ritualistic re-arrangement of the pieces of cars. In Love and Napalm and Crash, this primarily takes the form of the sexual fantasies of mingled human and mechanical parts in car crashes. In Concrete Island and earlier, The Drought, this takes the form of elaborate buildings contrived from wrecked and abandoned cars: Lomax, the Hardoon of The Drought, is an architect who creates a "bejewelled temple" out of the abandoned machines of civilization; when Robert Maitland, architect and protagonist of Concrete Island, has his man Friday build a shack for him, it is one made "out of the discarded sections of car bodies.”24 The working people of Ballard's own society rarely appear in his field of view, and when they do, they resemble Morlocks. In fact, when Ballard imagines a society "where," he tells us, "I would be happy to live”25 it is the world of Vermilion Sands, a weird hedonistic playground and sandbox for infantile artists who resemble incipient Eloi, safely isolated from the terrors of the city and totally untroubled by the intrusion of any workers except chauffeurs, maids, butlers, and personal secretaries. The working people of the rest of the world are no longer presented as the superstitious, treacherous, terrifying savages of The Drowned World and The Crystal World; they simply have disappeared from view altogether. Hence Ballard's imagined world is reduced to the dimensions of that island created by intertwined expressways on which individuals in their cellular commodities hurtle to their destruction or that apartment complex in which the wealthy and professional classes degenerate into anarchic tribal warfare among themselves. And hence Ballard accurately, indeed magnificently, projects the doomed social structure in which he exists. What could Ballard create if he were able to envision the end of capitalism as not the end, but the beginning, of a human world? Notes: 1. A perfect display of the shift in attitudes is presented in Orson Welles's 1976 film adaptation of The Food of the Gods; Welles leaves out altogether the main message about superhuman scientific achievement and thus converts Wells's paean to triumph science into a horror story of nature in disastrous rebellion against science. 2. See Manfred Nagl, Science Fiction in Deutschland: Untersuchungen zur Soziographie und Ideologie der phantastischen Massenliteratur (Tubingen: Tubinger Vereinigung fur Volkskunde, 1972). 3. Originally published as The Burning World (New York: Fawcett Medallion Books, 1964). The British version, greatly rewritten and expanded from fifteen chapters to 42, was published as The Drought by Jonathan Cape in 1965. 1 have used The Drought because it is more fully developed and more readily available. 4. Ballard, The Wind from Nowhere (New York: Berkley Medallion Books, 1962), p.48 5. Ballard, The Crystal World (New York: Berkley Medallion Books, 1967), p. 75. 6. Ballard, The Drought (Middlesex, England: Penguin Books, 1974), pp. 31-32. 7. 1 shall for convenience refer to this book as a novel, though its structure and intentions are clearly those of an anti-novel. Subsequently I shall cite, and therefore use the title of, the American edition, because it is far more readily available in this country and because interested readers ought to look at William Burroughs' preface to this edition. 8. For a general statement and application of this theory, see my article entitled (by the editors) "Chic Bleak in Fantasy Fiction," Saturday Review: The Arts, 15 July 1972, pp. 42-45. 9. Ballard, "The Overloaded Man," in The Voices of Time (New York: Berkley Medallion Books, 1962), p. 72. 10. Ballard, "Deep End," in Chronopolis (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1971), p. 312. 11. Ballard, The Drowned World (New York: Berkley Medallion Books, 1962), p. 44. 12. Ballard, "The Waiting Grounds," in The Voices of Time, p. 144. 13. Brian Aldiss, "The Wounded Land: J.G. Ballard," in Thomas D. Clareson, ed., SF. The Other Side of Realism (Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green University Popular Press, 1971), p. 122. 14. Ballard, "The Killing Ground," in The Day of Forever (London: Panther Books, 1971), p. 140. 15. Ballard, Crash (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1973), p. 13. 16. Ballard, Love and Napalm: Export U.S.A. (New York: Grove Press, 1972), p. 73. 17. Ballard, "The Subliminal Man," in Robert Silverberg, ed., The Mirror of Infinity (New York: Harper & Row, 1970), pp. 246-247. The following discussion of "The Subliminal Man" follows the lines of my introduction to that story in the Silverberg anthology. 18. Ballard, "The Subliminal Man," in The Mirror of Infinity, p. 261. 19. San Francisco Chronicle, 12 July 1970. 20. Andre van Dam, "The Limits of Waste," The Futurist, 6 (February 1975), 20. 21. Bradford C. Snell, "American Ground Transport," Hearings before the Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly of the Committee of the Judiciary, United States Senate, 93rd Congress, Second Session on S. 1167 (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1974), p. A-1. 22. Snell, p. A-2 and passim, pp. A-1 to A-103. 23. Snell, pp. A-2, A-3. 24. Ballard, Concrete Island (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1974), p. 162. 25. Ballard, "Preface," Vermilion Sands (Frogmore, St. Albans: Panther Books, 1975), p. 7.  H. Bruce Franklin John Cotton Dana Professor of English and American Studies H. Bruce Franklin was a factory worker, deck hand on a tugboat and a navigator and intelligence officer in the Strategic Air Command before finding his niche as a college professor, author and cultural historian. Since then Franklin has researched, written about and lectured on such far-ranging topics as the writings of Herman Melville, the history and literature of the Vietnam war, science fiction, the writings of prison inmates and most recently, the threat of overfishing “the most important fish in the sea,” menhaden. Franklin’s decades of work have established him as an internationally recognized interdisciplinary expert in several fields – and led to his selection as the 2006/2007 Provost’s Distinguished Research Scholar at Rutgers in Newark. Franklin, a resident of Montclair, N.J., is the John Cotton Dana Professor of American Studies at Rutgers-Newark, where he has taught American literature, science fiction and American studies since 1975. He is the author or editor of nineteen books and hundreds of articles. |

|||||||||||